Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

A Conversation with Tonči Čerina and Mia Roth in which We Barely Talked

A Conversation with Tonči Čerina and Mia Roth in which We Barely Talked

Mia Roth and Tonči Čerina, curators of the Croatian Pavilion, met with Aaron Smolar, Yidan Li, and Karla Andrea Perez to discuss their curatorial approach and how their installation relates to others in the biennale. Mia and Tonči did most of the talking, though we learned a lot about exhibition labor, finances, and materials, while also discussing spatial experiences and how ideas endure past their showcases.

MR: Mia Roth/ TC: Tonči Čerina/ AS: Aaron Smolar/ YKL: Yidan Karel Li/ KAP: Karla Andrea Perez

Our pavilion comprises two main components. First, there's the physical installation located at the Arsenale. Additionally, we have orchestrated a network of talks and workshops that occur beyond Venice, spanning various locations including Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia. Our aim was to establish a reciprocal relationship between what takes place in Venice and the themes explored within the pavilion, primarily related to education. We firmly believe that the future of architecture and design education necessitates a fundamental shift, encompassing changes to curricula, methodologies, and the topics we engage with.

Our physical installation and workshops draw inspiration from the Lonja wetland, an expansive protected area in Croatia, one of Europe's largest. It boasts a rich biodiversity and a significant human presence. Our exploration centers on the tools and patterns employed in the villages and towns that have developed in this area over centuries, reflecting a harmonious coexistence between the wild and the domesticated, human and natural. This enduring symbiotic relationship has thrived without one side trying to dominate the other. However, this delicate balance is now under threat, particularly due to increasingly severe floods in recent years, with water levels fluctuating by up to 4 or 5 meters. It's important to note that our intention is not to romanticize the past but to use this coexistence as a springboard for workshops that delve into speculative design. These workshops contemplate new relationships with technology, contemporary culture, and nature without privileging any single element.

The installation within the Arsenale itself encapsulates these symbiotic relationships. It combines a grid and a hovering biomorphic shape, creating an inner observatory. Integrated into this space are sampled bird sounds, a musical piece composed by an artist we collaborated with, and video material of the floods. It invites visitors to slow down and immerse themselves in this evocative setting. The grid and the biomorphic shape mutually reinforce each other, serving as an illustration of architectural coexistence. We've also introduced product design elements that reference traditional tools, furniture, and materials, which visitors can manipulate and use to engage with the space.

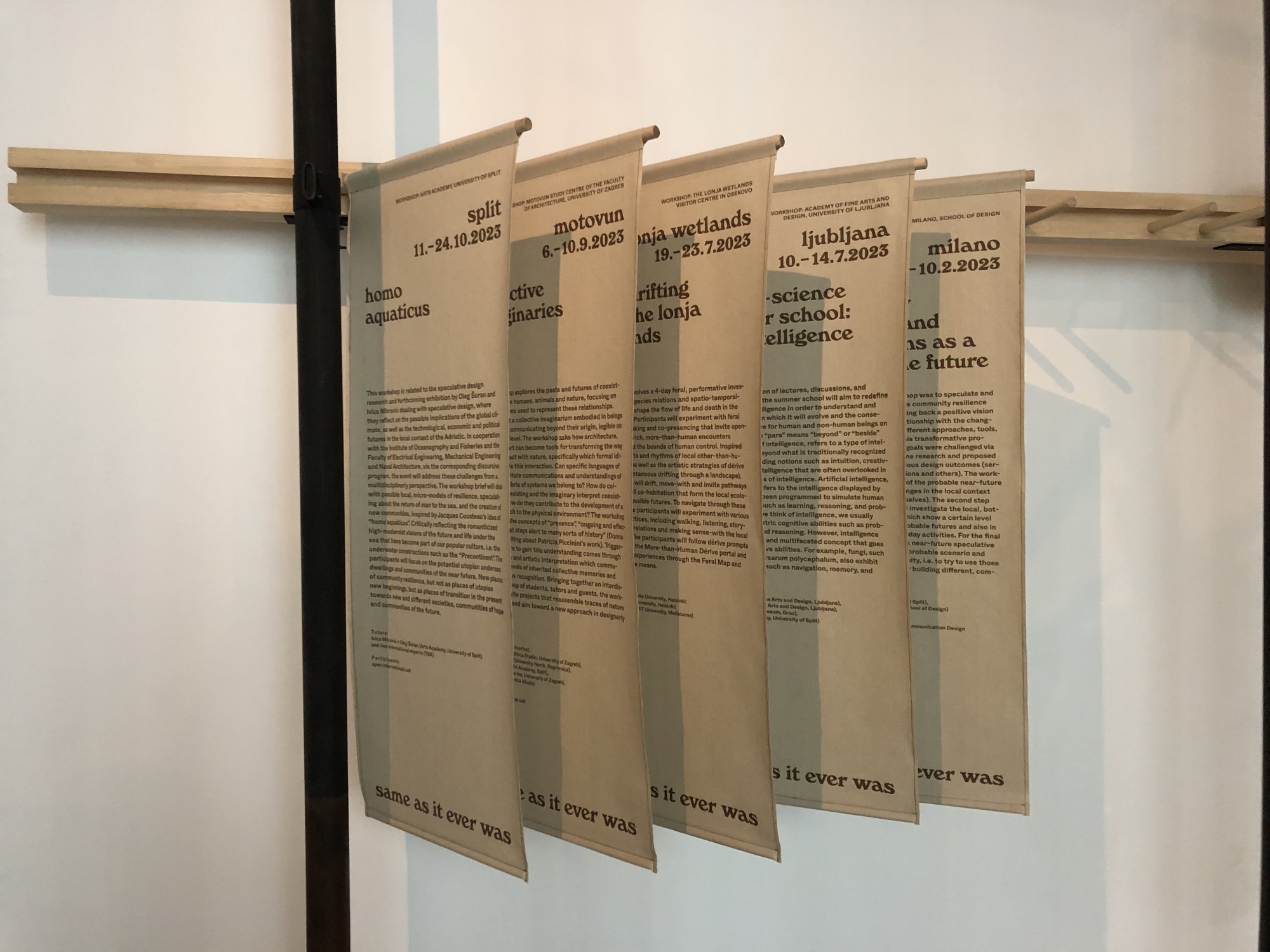

In terms of materials, we chose native ashwood from the wetlands for its flexibility and lightness. The entire structure is woven without additional binding material, making it highly pliable. The grid of the Pavilion alludes to the wooden pilings upon which Venice is built, many of which were sourced from Croatia, highlighting the historical connection between Venice and Croatia. These pilings are only treated up to a certain height, with the rest eroding over time, symbolizing the rising water levels and underscoring the link between Venice's floods and the environmental dynamics of the wetlands. Sustainability was a key consideration, and we planned for the installation's reassembly in Croatia. Regarding the curatorial aspect of the discursive program, we collaborated with designer Ivica Mitrović, founder of the SpeculativeEdu platform, who is organizing a series of workshops. One of these workshops has already taken place, and others are scheduled to happen in the Lonja wetlands, Ljubljana, Milan (with one workshop already completed), and Motovun in Austria. These workshops cover various topics and feature guests from international schools. They will soon be open to participants via an open call. The discussions encompass themes such as "Paraintelligence," alternative forms of communication, and interspecies communication.

Exploring different ways of connecting with nature. We've had Jaz Hee and Markéta from the Open Forest Collective, representing Aalto Helsinki and RMIT Melbourne, who led a workshop in the Lonja wetlands. In Ljubljana, we have a workshop called the Design+Science Summer School, hosted by the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts. All these workshops and more information about them can be found on our website. We're continuously adding new texts and content related to the topics of coexistence.

We've been pondering two aspects. In the Biennale, we've been coming here for decades to explore exhibitions of others' works, but there has always been a missing link. The Biennale lasts for around six months, and we realized that we can't merely bring a significant story that existed before us into the future by showcasing just one small part of it. So we contemplated the idea of a laboratory for the future. When we talk about a laboratory, it implies experimentation, a process where, oftentimes, you don't know the outcome of your experiments. That's the essence of a laboratory. Therefore, we designed the discursive part to serve as a continuous educational platform that extends before and after the Biennale.

Yes, both artistic interpretations of cooperation between species and the relationship between culture and nature, as explored in science, are key areas of interest for us. For instance, one of the first texts we commissioned was by a marine biologist who wrote about how survival of the fittest is not the predominant survival mechanism in nature, but rather cooperation between species. This challenges the dominant narrative related to progress, collaboration, and communication.

It's an idea that can be extended to human society, a paradigm shift away from the notion that the strongest individual alone will survive. Instead, it emphasizes the significance of collective cooperation. This is a crucial shift in the narrative of survival.

To quote James Baldwin regarding the British Pavilion, it's about the difference between those who aim to colonize the moon and those who simply want to dance under the moon, as if in front of an ancient friend. It points toward a paradigm shift in a different direction, one that embraces modesty and mutual respect. The Biennale is a culmination of numerous ideas and fantastic research, but it's not feasible for people to spend hours in each pavilion due to time constraints. To effectively communicate the profound ideas we're exploring, we need to operate on a subliminal, subconscious level, using spatial experiences. The installation in the Arsenale serves as a visual representation of the topics we're delving into. It conveys these ideas simply through its presence without the necessity of reading accompanying texts or artist statements. It communicates on a more visceral level.

It invites people to experience it physically, with their bodies, and immerse themselves in the atmosphere. Our aim is to motivate visitors to explore further when they have the time to do so.

Could you provide more insight into the logistics involved in creating the pavilion? How did you plan for the assembly and disassembly of the installation, and when did you become aware of the allocated space?

We were informed about the allocated space relatively early in the process. As you might know, the history of the Biennale exhibitions includes dedicated pavilions for each nation at the Giardini, whereas the spaces at the Arsenale are rented. This year, our Pavilion is shared by two countries, and we had previously used this space for the Croatian Architectural Biennale. In terms of logistics, we needed to plan meticulously, taking into account the challenges of transporting materials by boat within Venice. Our primary focus was on sustainability and reuse. The steel elements used in the structure were designed for easy disassembly, packing, and reassembly, thus minimizing waste. Due to the confined space and the shared environment with other participants, precision was crucial. Some countries, such as the German Pavilion, even centered their installations around utilizing materials left over from other pavilions.

To add to that, we chose steel for part of the pavilion's construction instead of wood, as wood could deform due to humidity. Also, our installation is in constant dialogue with the exhibition space. We aimed to occupy the space comprehensively, not merely displaying elements in a linear fashion. We wanted to fill the space to its fullest, making its presence felt when visitors step inside.

As for the logistics, most of the work was carried out by our team, except for the steelworkers. We had two workers installing the steel structure and two working on the flooring and electrical aspects. The rest of the work was done by us. For instance, we wove the wooden elements ourselves, along with two collaborators from our office. There's a very specific technique involved that gives them a nest-like or cocoon-like appearance. We had to be hand-on because although it doesn't symbolize any specific entity, we had a precise vision of how we wanted it to look. Other work was handled by Italian workers.

It's interesting to hear that you brought workers from your country to Venice, which is not a common practice among participants.

Indeed, it made sense for us financially. Whenever someone from Croatia traveled to Venice, we would make sure to maximize the use of their vehicle, and it was never empty.

The idea was to have our team actively involved in the process. We wanted to maintain a high level of control over the production, actively participating in various aspects ourselves.

Because we want to disassemble the installation and reassemble it in Croatia. Bringing our own team allowed them to become intimately familiar with the project, ensuring they know how to carry out these processes.

Additionally, it was crucial for us to source all materials locally, directly from the environment we were drawing inspiration from. The wood came from the wetlands, and the steel was fabricated in a workshop close to Venice, reducing transportation impact.

You mentioned the floor and the bird sounds earlier. I noticed a consistent creaking sound while in the pavilion. Was that intentional?

The creaking sound was partly intentional. We carefully considered the materiality of the flooring and its interaction with the plates in the space. Our intention was to create a resonant relationship between them. However, the sound itself is synthetically produced. It mimics the clattering sound of storks, as these birds are known for their distinct percussive calls. The sound piece, composed by an artist, is presented in three multi-channel compositions. Our aim was to blend elements of the natural world with those of human creation, highlighting the interconnectedness and blurred boundaries between the two. We strived to emphasize that everything is intricately linked, and these boundaries should not be rigidly defined.

Your emphasis on subliminal communication is intriguing. Have you encountered any other installations at the Biennale that align with your vision?

The Irish Pavilion for sure. And certainly, we've encountered several remarkable installations throughout the Biennale. Each pavilion offers a unique atmosphere and experience, often tapping into subconscious elements and conveying powerful messages. Distinguishing the impact of specific installations can be challenging because each one immerses you in its distinct world, evoking a range of emotions and ideas.

We think this year's Biennale is very successful. It advocates for a soft and sensitive approach, urging a transformation in the architectural paradigm through accessible and relatable means.

It's calling for a different narrative and a more compassionate perspective.

I’m also interested in the fabric pouches along the back wall in the pavilion. Can you elaborate on that?

The fabric pouches draw inspiration from traditional tools used in the wetlands. We've incorporated them into the pavilion to serve as vessels for distributing leaflets about our pavilion. Each leaflet features an image of the environment. On the reverse side, we've placed posters made of the same fabric, announcing the topics of our workshops. Visitors can also interact with the chairs and benches, which are designed for easy assembly and disassembly. Our aim was to create an interactive and physically engaging experience for visitors, making the Pavilion more accessible and inviting.

Additionally, we're in the process of creating a catalog that compiles the outcomes of our workshops and includes texts from the Biennale. This catalog will serve as both a guide and a source of reflections, extending the impact of our pavilion well beyond the event. We've divided it into three parts: the Present, Crisis, and the Future.

It's essential for us to ensure that the knowledge and experiences gained from our pavilion continue to benefit others long after the Biennale concludes.

This approach echoes the gap you mentioned, between the ephemeral nature of the Biennale and the enduring importance of the ideas.

Yes, we want to establish a reciprocal exchange with various environments.