Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

Neighborly BehaviorNicolay Duque-Robayo

Neighborly BehaviorNicolay Duque-Robayo

The designation of neighbor proposes a relationality between two objects, one that begins with proximity, with spatial dimensions. The good neighbor looks after plants and picks up the mail while one is out of town. There is also the neighbor who, despite multiple requests and confrontations, ceaselessly plays loud music into the late hours of the night. No matter the terms of the arrangement, the concept of neighbor itself establishes a possibility of connection. For some, the absent neighbor is most desirable, providing a moment of solace in the comfort of one’s own home. For others, a sense of community extended by their neighbors enables the boundaries of the home to expand beyond the confines of one’s apartment or the walls of a building. For the 18th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, the Swiss Pavilion presented Neighbours, a study on the history between their Bruno Giacometti building (1952) and the Carlo Scarpa-designed Venezuela Pavilion (1956). As the only national pavilions sharing a wall, the Giacometti-Scarpa edifice presents a unique opportunity to study the relationship between two national representations—presumed to be distinct—as materially and historically interwoven.

Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung, the curators of the Swiss Pavilion, propose a relational dialogue between the two national representations. This dialogue between the pavilions takes place in the catalog for the exhibition, and the spatial interventions enacted on the Swiss pavilion. Despite their proximity to one another, the Venezuelan and Swiss Pavilions remain distinct from one another through their programing and unique facades, yet present as cordial colleagues next to one another. By converging their spatial relationality to one physical space, Sander and Ursprung aim to illustrate how the production of a better tomorrow requires understanding those around us. In a catalog accompanying the pavilion, they write, “We learn only through contact with others. Pavilions, like all of us, should take more care of each other.”Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung, “Manifesto,” in Neighbours: A Manifesto, a Play for Two Pavilions, and Ten Conversations, ed. Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung (Zurich: Park Books, 2023): 7. For the curators, sites and people are not so different in their neighborly relationships to their immediate surroundings. By personifying the pavilions, an agency is imposed onto the nation-state, a metonym for both cultural and diplomatic relations. Underneath this presumption is the belief that if we as people understand the people that surround us, whether in spatial or historical proximity, a better tomorrow is possible.

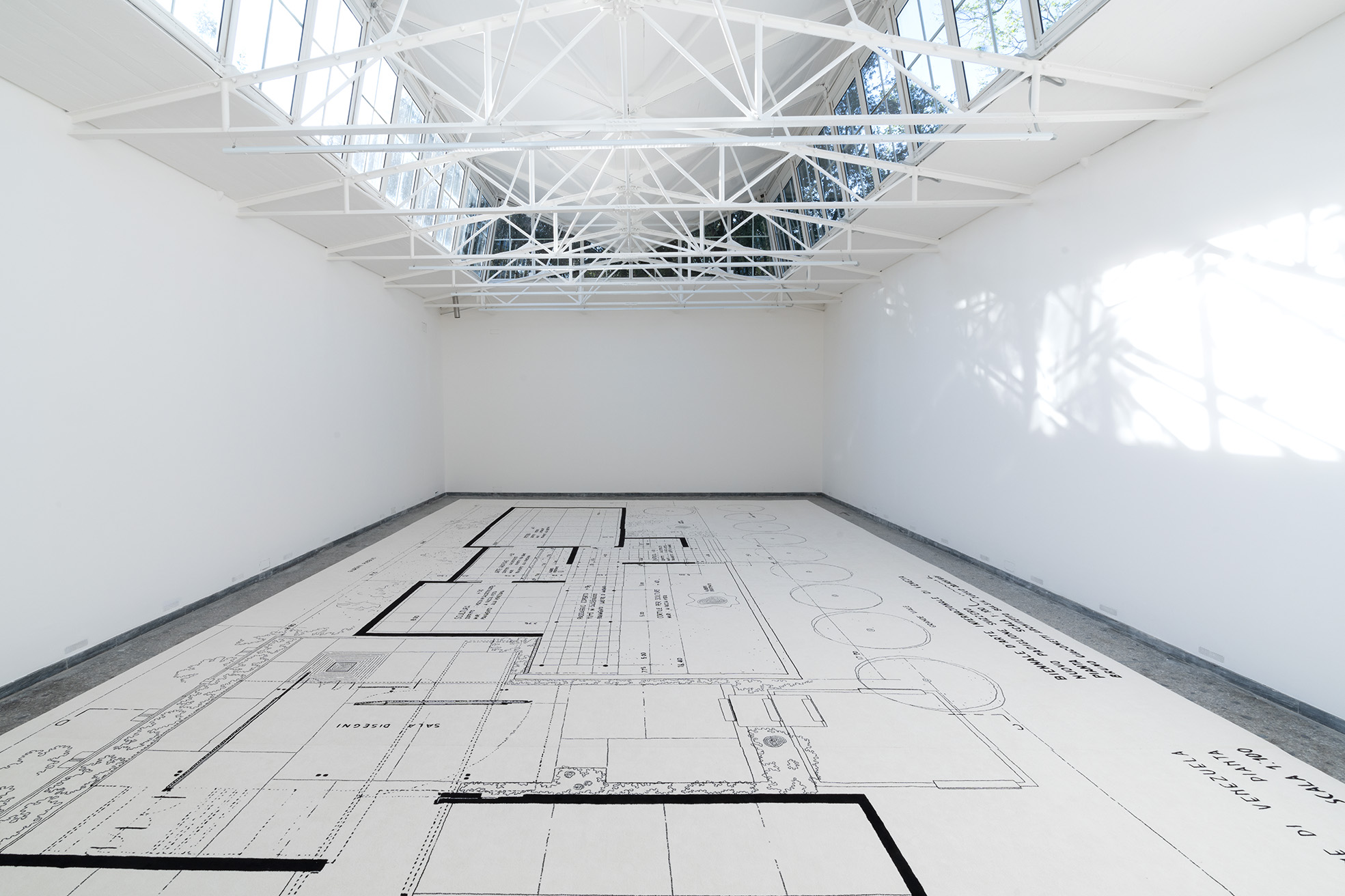

Upon entering the main hall of the Giacometti-designed pavilion, one finds that the Swiss curators opted to showcase their project not with the usual didactics of wall text or introductory video. Rather, a large carpet printed with a drawing of the combined Swiss and Venezuelan Pavilions’ floor plan occupies much of the room. Implicitly, visitors are invited to walk on the carpet, occupying the space of both pavilions on two different registers. Yet in its placement on the ground, the carpet challenges the visitors’ ability to visually consume the collaged plan from a single location: it requires them to walk the length of the room to fully grasp the intervention of the curators on the site. The floorplan illustrated on the carpet presents the two pavilions as if effortlessly combined, evocative of a single structure planned in conjunction by the two architects. It is not until a close examination of technical details, such as the rendering of the trees or the respective title blocks, that what is woven onto the carpet is fully exposed: two plans for two pavilions blended to become one. The boundary between the pavilions collapses through this fusion of their technical drawings, suggesting the treatment of two adjacent buildings as a single unit.

However, this proposal of continuity between the Swiss and Venezuelan Pavilions does not lie simply on theoretical or graphic terms. Despite not sharing a party wall, the two buildings do share a gap between walls mere inches apart. For this iteration of the Biennale, a portion of the Swiss wall was temporarily disassembled to enable a seamless flow between the two pavilions. While the stylistic characteristics of each pavilion give away where one ends and the other begins, the opening of the brick wall enables the visitor of the Biennale to perceive both sites as a united entity—an experience aided by the already minimal presentation of material by the Swiss curators. The proximity of the two pavilions, with a gap mere inches apart, hints at their neighborly relationship. The Swiss gesture to open a passage between the two pavilions employs their spatial proximity towards more than spatial connection; rather, it is a nod towards the possibility for connection that may begin with the spatial, but has the potential to extend beyond the distance of either the grounds of the Giardini or geopolitical state borders.

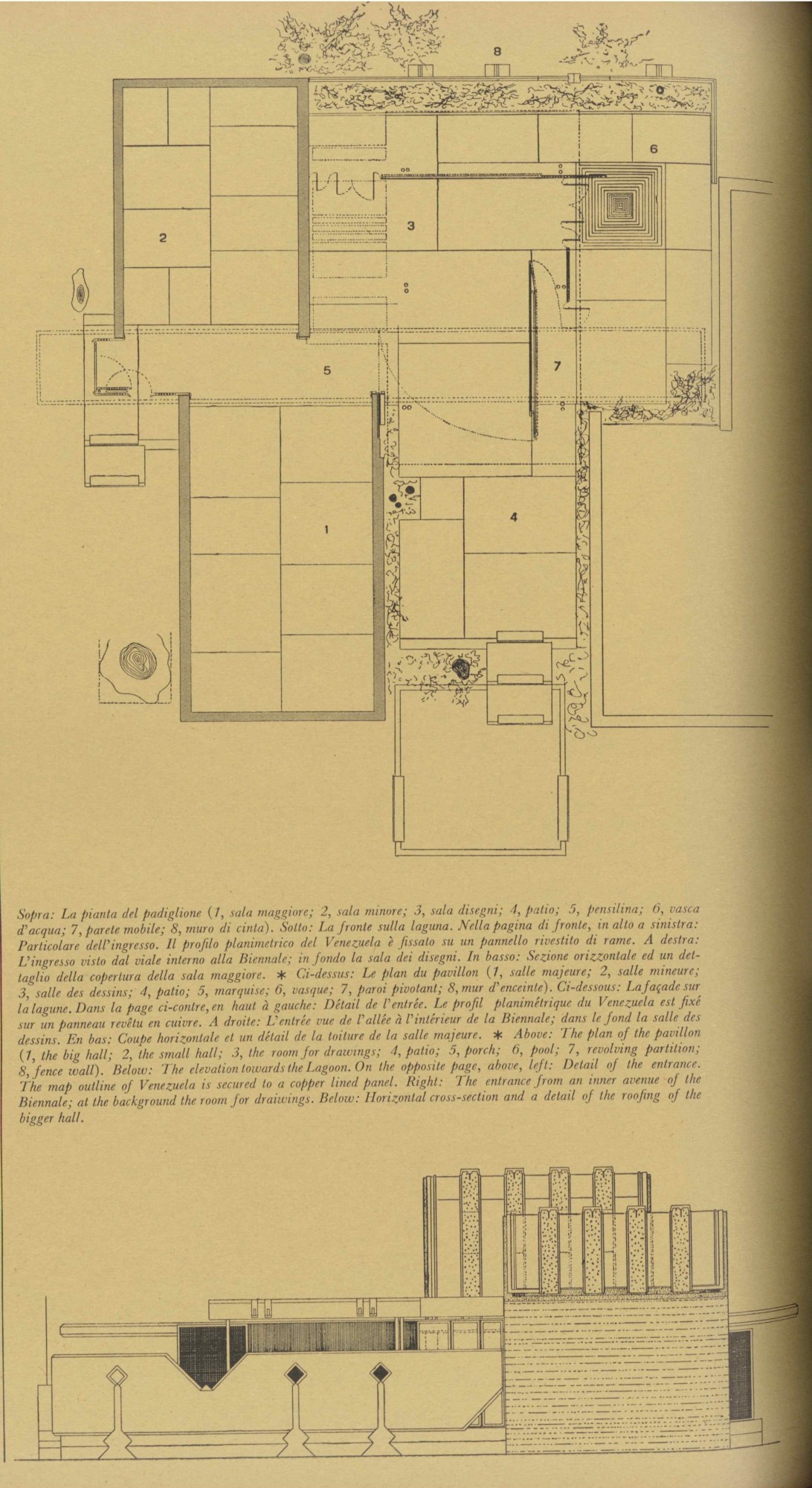

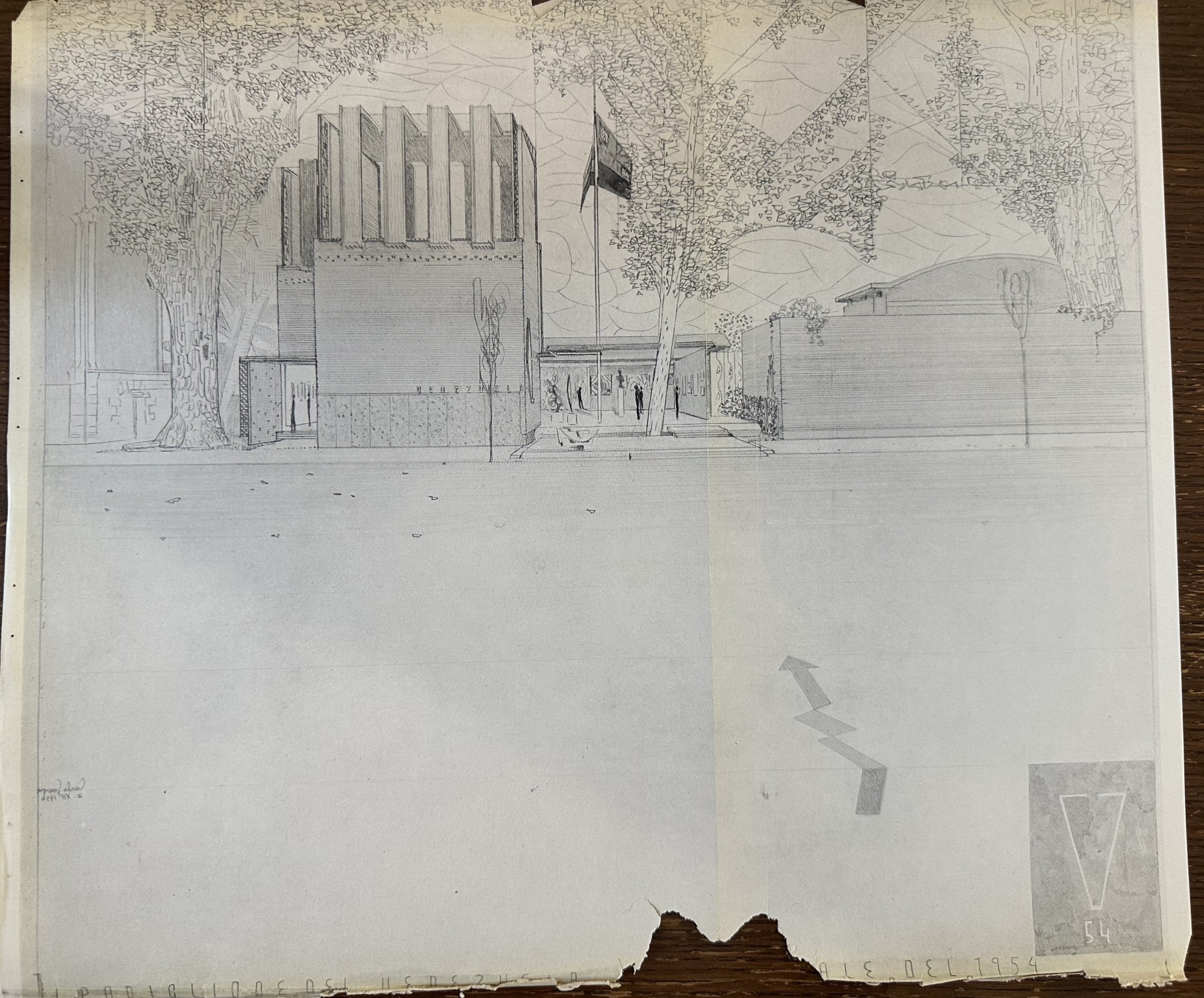

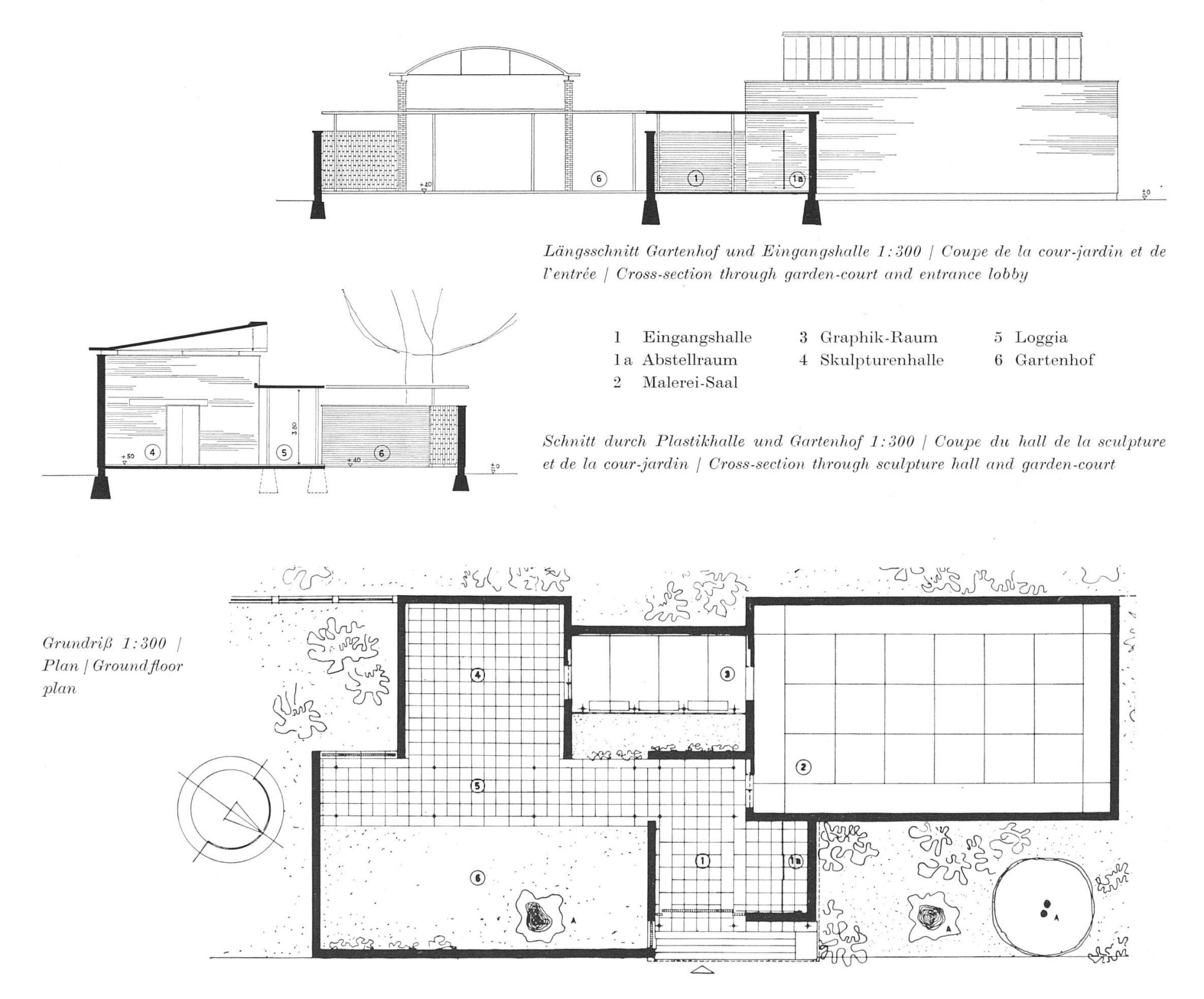

Built in 1952 and 1956 respectively, the Swiss and Venezuelan Pavilions in the Giardini allude to the unique sociopolitical crux of the Biennale during the postwar period. Along with the Giardini’s ticket kiosk—also designed by Scarpa in 1952—the two pavilions mark the Biennale as an enterprise concerned and entangled within international affairs. As strategically requested by Swiss authorities, a new entrance to the Giardini near the planned Swiss Pavilion reoriented the choreography of Biennale visitors around Scarpa’s ticket kiosk.Marco Mulazzani, Guide to the Pavilions of the Venice Biennale since 1887 (Milano: Electa architecture, 2014), 90. Built concurrently, the spatial tension between the Ticket Kiosk and the Swiss Pavilion germinated a relationship between Scarpa and Giacometti’s built works–and between the architects themselves. Inaugurated on 14 June 1952, in accordance with the 26th edition of the Art Biennale, Giacometti’s design served as a point of departure for Scarpa when he began work on the Venezuelan Pavilion a year later.Mulazani, 100. A plan of the Venezuelan Pavilion published in an October 1956 issue of Casablanca, just a few months after the Pavilion’s June completion, denotes the adjacent Giacometti building by including the walls—albeit absent of any detail. In an elevation drawing dated to 1954, Scarpa presents a Venezuelan Pavilion inhabited by multiple visitors, in proximity to the rendered walls of the Swiss Pavilion next door. Nearly seventy years later, Sander and Ursprung’s evocation of the two buildings’ intertwined history correctly illustrates that the pavilions share a relational connection that exceeds spatial proximity. An archival photograph of Giacometti and Scarpa suggests that the two neighbors did not just stand side by side but acknowledged each other beyond the products of their architectural labor.Neighbours: A Manifesto, a Play for Two Pavilions, and Ten Conversations, ed. Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung (Zurich: Park Books, 2023): 31. Rather, the gap filled between the two pavilions is brimming with potential, with possibility for connection.

Notably absent from Sander and Ursprung’s Swiss Pavilion curatorial project is the Venezuelan perspective. Language in the Swiss Pavilion’s catalog alludes to bureaucratic red tape preventing the curators from collaborating with their Venezuelan counterparts. “We see the two Pavilions as a spatial continuity. We open up the brick enclosure of the Swiss courtyard. (The curators of the Venezuelan Pavilion have been informed).” Neighboours, 7. It is unclear if the limitation is a stipulation of the Biennale, or if it results from geopolitical concern from Swiss authorities to cooperate with the pavilion as a representative of the regime of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. While it is unreasonable to demand from the Swiss curators to work against this possible bureaucratic hurdle—particularly under the notorious time constraints presented to participants of the Biennale—the absence of a Venezuelan voice puts into question what it means to “open up” this “spatial continuity.” The exhibition catalog attempts to resolve this absence, underscoring the anxiety of the Swiss curators to avoid a paternalistic gaze. A photo-essay and interviews pertaining to Venezuelan history conducted in the summer of 2022 with historian Margarita Lopez-Maya and architect Elisa Silva, both based in Caracas, deliberately incorporate a perspective of the region despite the omission of any details in the texts pertaining to Sander and Ursprung’s intervention for the Biennale. In the context of “opening up” conversation between the two delegations, the inclusion of the interviews into the catalog for the exhibition posits an unclear resolution to an alleged back-and-forth.

In contrast to the Swiss Pavilion, the Venezuelan project for the 2023 Biennale looks inward to its own architectural modernist history. Titled Universidad Central de Venezuela, Patrimonio de la Humanidad en recuperación. Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, curator Paola Claudia Posani presented a history and preservation assessment of Carlos Raul Villanueva’s iconic mid-twentieth century university complex in the country’s capital. Largely relying on exhibition didactics written in Spanish, the Venezuelan exhibition serves as a testimonial to the value and importance of the Ciudad Universitaria to the world of architecture. Further contrasting the Swiss Pavilion, the Venezuelan project lacks either a catalog or a public-facing website for the exhibition. Even a cursory search on the internet regarding Venezuela’s participation in this edition of the Architecture Biennale brings up abundant reporting regarding the Swiss Pavilion instead. Understandably, resources and fast timelines for projects occupying the Giardini complicate the possibility of coordination across national pavilions. Yet an eerie discrepancy arises when one considers how the Swiss Pavilion aims to celebrate its ability to think beyond geopolitical borders, while the Venezuelan Pavilion still fights to assert itself as an important figure within the history of twentieth century architecture. Present in this dynamic is nothing short of the played-out story of mid-twentieth century developmentalism, where a so-called developed nation enlightens the condition of a country of economic underdevelopment. While echoes of dependency theory remain in a contrast of the two projects, a more complicated story arises by attending to the sociopolitical conditions that brought on the construction of the Venezuelan Pavilion and the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas.

Both Scarpa’s Venezuelan Pavilion and Villanueva’s Ciudad Universitaria were designed and built in a period of economic flourishment for the country as its vast oil reserves supplied allied efforts during and after World War II. Coupled with its rise to prominence in the global stage during the postwar period, the figure of the country’s dictatorial leader, Marcos Perez Jimenez, haunts both architectural projects. Historian Lisa Blackmore frames the period under military dictatorship (1948-1958) as a period of “spectacular modernity.” Building on Fernando Coronil’s study of the relation between the Venezuelan nation state and oil, for Blackmore, spectacular modernity “refers to the entanglement of the politics of dictatorship with aesthetic innovations in spatial arrangements and visual culture.” Lisa Blackmore, Spectacular Modernity: Dictatorship, Space, and Visuality in Venezuela, 1948-1958. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017), 19. Perez Jimenez’s Venezuela planning framed the country as modern through an ocularcentric framing of the urban fabric of the capital. Caracas became both the spatial and aesthetic storefront of power for the military regime, positioning efforts of urban and architectural modernism as a battleground to assert its legitimacy as a nation. Blackmore’s study attends to architecture, graphic design, and infrastructure as vehicles for the legitimization of Venezuela as a force in the geopolitical sphere. Perez Jimenez, a man known for brevity and absence in the media, “focused on providing concise information and figures to corroborate progress and reiterated that Venezuela was becoming ever more wealthy, dignified and strong so as to induce national pride.”Blackmore, 136. The visual shorthand of modern architecture further cemented to Venezuelans, and those who witnessed the construction boom as design projects were circulated through media, the reach and power of Perez Jimenez and oil.

Albeit geographically distant, the Venezuelan Pavilion in Venice ultimately engages with the agenda of international relations proposed by Blackmore. If the architectural works in Caracas, such as the Ciudad Universitaria, further legitimized the dictatorial power of Perez Jimenez to Venezuelan citizens, the concurrent construction of Scarpa’s pavilion legitimized Venezuela in the global stage. As the first country in its region represented with a permanent pavilion in the Giardini, Venezuela’s stake in the Biennale situates it as a financially and culturally globalized player in the postwar period. Nearly seven decades apart, the completion of the Venezuelan Pavilion in 1956 and its exhibition for the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale use the language of twentieth-century architectural modernism to appeal for the larger contributions of the Latin American nation to the world. Where the Scarpa pavilion remains a constant between this chronological gap, the current socioeconomic condition of Venezuela reframes the plea for urgency. In 1956 the pavilion sought to use its financial resources to assert Venezuela’s strength as a rising geopolitical power. In 2023 the pavilion implemented its cultural capital to underscore its contributions to the architectural legacy towards the preservation of Venezuelan icons of architectural modernity amidst political and financial crises.

From the Swiss vantage point, the curators’ material and theoretical intervention into Giacometti’s structure is a gesture toward dissolving national borders. Albeit an altruistic gesture to move beyond identitarian prescription of value within the Biennale, such framing reinforces dichotomies of Global North and South when juxtaposed with the project presented in the pavilion just next door. A 1951 floor plan of the Swiss Pavilion depicts Giacometti’s design surrounded by trees, with the plot of land that would later be occupied by the Venezuelan Pavilion as the space for the north arrow. To frame Sander and Ursprung’s project as condescending or paternalistic is dismissive of both the creative effort of the Swiss delegation and the complexity of postwar period cultural conditions. By prioritizing the sensory experience of the visual, by opening the wall that separates the two buildings, the Swiss curatorial team reinforces an architectural prerogative to conflate the phenomenological with the experiential. The framing of Neighbours couples the history of the two pavilions, but the project showcased in the Swiss Pavilion never moves beyond this call to attention. There is no demand to cross the boundary. To visually comprehend the gesture towards the possibility of action, Neighbours employs a rhetoric not unlike Perez Jimenez’s use of modern architecture as proposed by Blackmore’s “spectacular modernity.” They both reflect the power embedded within the visual spectacle emblematic of the architectural project. As a neighbor, the Swiss delegation is aware of the present and historical implications of spatial proximity; nonetheless, a hesitancy to knock on the door prevails.

Walking through the dismantled wall from the Swiss Pavilion alters the experience of the Venezuelan Pavilion. Instead of revealing the open patio opposite the Scarpa-designed entrance, the wall opening only leads from the Swiss side to a concrete wall of the Venezuelan Main Hall. The experienced choreography between the two spaces is not one of mere happenstance—nor is it a moment of historical serendipity between two architects—but the reality of managing the neighbor-like implications of two buildings situated on a single site. The collage of the Scarpa and Giacometti pavilions is not merely additive, or a melding of two complementary sides of the same story. Instead, by opening the wall, the Swiss Pavilion provokes as many questions about the interrogators as it does about the site. While an accepted academic exercise, to provoke a question and invite conversation appears to be the limit of the Swiss project rather than a threshold. The Venezuelan Pavilion finds itself in the position to remind audiences of their contribution to twentieth-century architecture, a plea to preservation of world heritage. This plea is not just for Villanueva’s Ciudad Universitaria, as the Scarpa Pavilion has experienced vandalism and decay throughout the decades.Mulazzani, 102-103. From the perspective of the Venezuelan Pavilion, the Swiss edifice is but a gawking neighbor, peeping through a hole of their own making.