Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

The Blue Hour: Pilgrimage and Architecture’s ‘Moral Community’Zachary Torres

The Blue Hour: Pilgrimage and Architecture’s ‘Moral Community’Zachary Torres

In 829 CE, the relics of St. Mark were smuggled from Alexandria into Venice, fulfilling the prophetic legend that the saint would one day rest on the island where he had once sought shelter from a storm. Lacking its own historic martyr and needing to enhance its political and spiritual power, Venice, instead, gathered into its watery territory the relics of saints from North Africa, Asia Minor, and the Levant.As a "second generation" settlement, Venice was not populated during the initial wave of Christianization, and thus lacked a historical martyr, unlike most other Italian cities. It was not until after the Fall of the Western Empire, around 811 CE, that the lagoon’s marshy islands began to be permanently inhabited; John Osborne, “Politics, Diplomacy and the Cult of Relics in Venice and the Northern Adriatic in the First Half of the Ninth Century,” Early Medieval Europe 8, no. 3 (November 1999). This translation of relics from the East not only salvaged them from Islamic rule but also bestowed divine protection upon Venice and other European cities—a protection, it was believed, the East no longer needed.Deborah Howard, “Venice as Gateway to the Holy Land: Pilgrims as Agents of Transmission,” in Architecture and Pilgrimage, 1000-1500: Southern Europe and Beyond, ed. Paul Davies, Deborah Howard, and Wendy Pullan (Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2016). 93. After the First Crusade, “the translation of relics became a regularized event in Venetian devotional life.” Following St. Mark, St. Zacharias, St Anastasia, St. Isidore, St Lucy, St. Helen, and St. Theodore were some of the most prominent saints to have their relics relocated to Venice. As Osborne notes, because the city possessed the body of an apostle, the “Venetians stood in spiritual debt to no one;” “Politics, Diplomacy, and the Cult of Relics,” 386. As Osborne notes, because the city possessed the body of an apostle, the “Venetians stood in spiritual debt to no one;” “Politics, Diplomacy, and the Cult of Relics,” 386. Yet, despite possessing the body of an apostle and the relics of countless other early Christian martyrs, Venice never evolved into a major pilgrimage destination like Rome, Canterbury, or Compostela. Rather, Venice fashioned itself as the “point of embarkation” for meticulously organized pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Osborne, “Politics, Diplomacy, and the Cult of Relics,” 369. See also S.D. Sykes, “Did the Venetians Invent the Package Holiday?,” Historia, August 10, 2017, https://www.historiamag.com/venice-sdsykes/; Howard, “Venice as Gateway to the Holy Land,” 95-96. Nonetheless, Venice aspired not merely to become a way-station for pilgrims but a heterotopic reflection of the Holy Land itself. With its accumulation of relics and sacred objects, along with the newly built churches that housed them,Medieval Venetians built new churches for the translated relics. Often located in the vicinity of the Arsenale (the contemporary site of the Biennale), these churches were designed after structures in the Holy Land, thus serving as mirrors or glimpses across the sea; Howard, “Venice as Gateway to the Holy Land,” 103. Venice supplied European pilgrims with spiritual entertainment while they awaited their ships’ departures. This accumulation of relics set Venice up as a mirror of the Holy Land, as its own sacred city—albeit, not as a destination, necessarily, but as a preview of a forthcoming world: a vision of the future.

Like medieval Venice, exhibitions are also sacred spaces. As mirrors onto reality, they at once reflect a community’s hopes, ambitions, and utopian visions, while condensing those same hopes and visions into an easily understood image. To the faithful, such paradisiacal images are often more real than the profane world they seek to portray. Exhibitions, too, are like such icons. Just as the architecture of the church functions as a filter through which reality must pass to attain its full divine potential, exhibition spaces deconstruct the “real” world to make it more legible. In so doing, they are spaces of critique, analysis, and speculation. They are confessional sites that gather the faithful (and the infidel) and employ sacred narratives to preach messages of salvation (or doom). Both religious and exhibition spaces are witnesses to the complexities, contradictions, and permutations of human culture.

The biennales of Venice can thus be read both as continuing the translation of sacred knowledge from othered elsewheres and as pilgrimage destinations in their own right, as they gather a discursive community and operate as social condensers and didactic disseminators. Medieval pilgrimages to the Holy Land likewise gathered large crowds at certain times of the year to worship, with prayer serving as a type of unifying discourse, a lingua franca. Like the biennales, pilgrimages were also moments of experiential learning, dialogue, and international socialization. More than a single destination though, biennales—as exhibitionary amalgamations—offer a plethora of surreal visions. In this sense, the Venetian biennales parallel the city of Venice itself; they are mirrors onto reality just as Venice is a mirror of the the Holy Land, which itself is a territorial consolidation of various worldviews, gathering as it does a multitude of confessions and their architectural projections of divine utopia. But like the Venice of the Middle Ages, the 18th Architecture Biennale is only the point of embarkation, offering us merely a glimpse of the plethora of divine visions we, as a larger human community, can construct together.

The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale presents itself as a glimpse into the future, but it is a future rooted in an exploration of the past. Just as medieval Venetians collected the relics of a Christian past to project the reflection of a near future, the curators, architects, and artists of the biennale follow “detours through the past … to make ourselves anew”—a claim made by sociologist Stuart Hall, who is quoted throughout the exhibition. This past is embedded in memories of the sacred that employ not Christian mythology but indigenous understandings of the earth’s sanctity and syncretism of the human community. While Venetians had once engaged in a thaumaturgic trade to bolster their maritime power,Howard, “Venice as Gateway to the Holy Land: Pilgrims as Agents of Transmission." today, director Lesly Lokko and her curatorial team invite the architectural community to “pilgrimage” to the biennale to contemplate epistemologies, methodologies, and mythologies that lie beyond the confines of Western knowledge, empowering our capacity to confront carbon-capital imperialism. Rather than a translation from East to West, Lokko proposes a flow of ideas from South to North.

The pilgrim's glimpse toward a utopic future is present in Lokko’s curation of the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, particularly in the Corderie’s entry sequence, which, I argue, functions as the preliminary, or liminal, space of a pilgrimage. Employing Venice’s legacy as a mirror of the Holy Land, and gesturing toward the sacred motifs present throughout Laboratory of the Future, I consider how exhibitions like the biennale establish themselves as sites of ritual gathering and discursive reflection. I propose the Venice Architecture Biennale be thought of as a pilgrimage destination necessary for the continuous revitalization of architectural discourse—just as pilgrimages stimulated Christian travelers and enriched medieval European culture. Lesley Lokko’s curation of the Biennale, though, seeks to break with hegemonic narratives that consider the pilgrimage as merely bidirectional, offering instead, circuitous pathways and divergent voices. Lokko does away with singular narratives; she discards the totalizing view that is the (monotheistic) Western gaze, offering us other vantage points from which we can glimpse not a heavenly utopia, but a constellation of overlapping divine realities. If the medieval pilgrimage coalesced a “moral community”—as historian Barbara Kowalzig says Barbara Kowalzig, “Festivals, Fairs and Foreigners: Towards an Economics of Religion in the Mediterranean Longue Durée,” in Pilgrimage and Economy in the Ancient Mediterranean, ed. Anna Collar and Troels Myrup Kristensen (Boston: Brill, 2020), 305. —then Lokko’s curatorial intent is to invite a broader array of voices and research practices into the discipline, collecting not a mirror but a kaleidoscope of possible futures.

I. Embarking

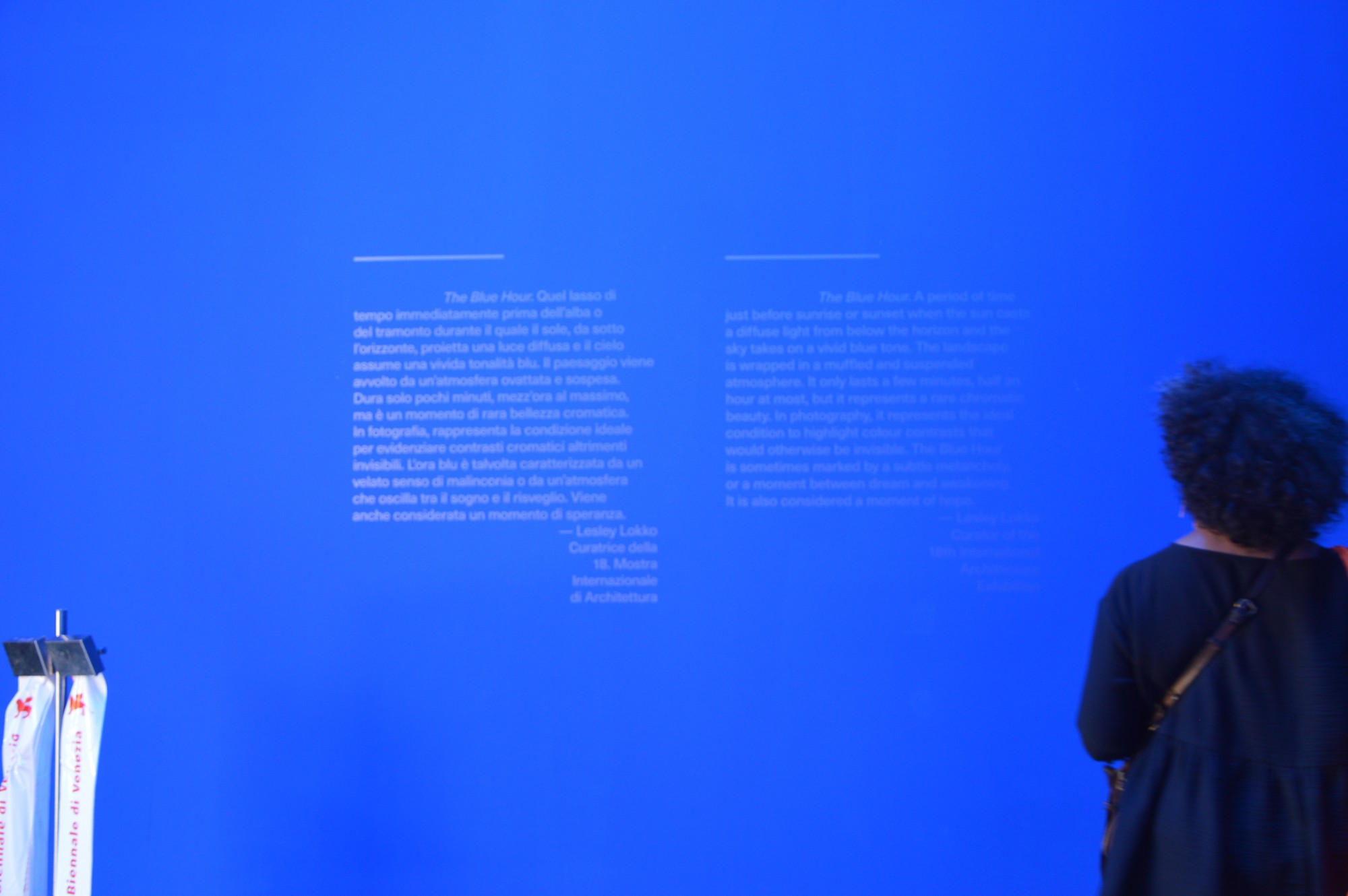

A pilgrimage mirrors the cycle of life and death in which the pilgrim dies to their worldly life, embarks on a spiritual journey, and arrives at enlightenment or salvation. In her curation of the 317 meter-long Corderie, Lokko invites visitors to undergo a similar experience of death and rebirth. This is made immediately apparent in the vestibule, which is awash in vibrant blue. This particular hue may initially seem overwhelming, but it exudes a calming and centering effect. It is overpowering in that it disengages visitors from the exterior world of Venice’s winding alleys, immersing them instead in a contemplative attitude. Blue is a calming or melancholic color and one that is often associated, at least in a Christian context, with heaven and the divine. Yet, this is not just blue but the liminal blue of the golden hour. In her didactic text for the room, Lokko elaborates,

The Blue Hour. A period of time just before sunrise or sunset when the sun casts a diffuse light from below the horizon and the sky takes on a vivid blue tone. The landscape is wrapped in a muffled and suspended atmosphere. It only lasts a few minutes, half an hour at most, but it represents the ideal condition to highlight colour contrasts that would otherwise be invisible. The Blue Hour is sometimes marked by a subtle melancholy, or a moment between dream and awakening. It is also considered a moment of hope.Lesley Lokko, The Blue Hour, in the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, Laboratory of the Future, 20 May - 26 November 2023.

Blue, as the color commonly used to represent water, envelops visitors as they enter the biennale’s vestibule, immersing them in its baptismal powers. With The Blue Hour, Lokko generates a sacred atmosphere by freezing time and tying it to place. Within this vestibule, the short daily glimpse of the blue hour is prolonged indefinitely, transforming it into a purgatorial space of preparation before one engages the exhibitions that lie beyond.

The Blue Hour is the first step on the journey of pilgrimage. It functions as the threshold where pilgrims die to their worldly life and enter the liminal space of not yet knowing, shedding cultural biases and dismantling established epistemological structures. As Anatole France’s quote located above the doorway reminded us, “All changes, even the most longed for, have their melancholy; for what we leave behind us is a part of ourselves; we must die to one life before we can enter another.”Anatole France, originally in The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard, published in 1881, and quoted in The Blue Hour. In freezing the blue hour, Lokko equips the visitor with its power to reveal dissimilarities, enabling them to scrutinize the exhibits beyond in a critical framework, contrasting them with the prevailing Western intellectual and cultural hegemony. While imbued with a sense of melancholy, The Blue Hour is also hopeful: In its Cistercian simplicity, it fosters anticipation of what lies ahead, all without generating presumption.

While The Blue Hour displaces one from time, place, and self, the subsequent room, a circular hall adorned with mirrors, returns the visitor to their body while reflecting it indefinitely at multiple scales. As Michel Foucault notes in his work on heterotopias,

From the standpoint of the mirror, I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 24.

Both exhibitions and pilgrimages are types of virtual heterotopic space that run parallel to the real space of the outside world, enabling individuals to perceive it differently. As medieval Venice sought to mirror the Holy Land, Lokko’s vision for the biennale is to be a mirror of an alternative reality and a glimpse into a possible near future where North/South and East/West geopolitical bi-directionality crumbles into a more complex and enmeshed understanding of our human relations. Just as Venetians translated relics to attain divine protection, Lokko challenges geopolitical bi-directionality by inviting actors from the Global South and its diasporas to share their pasts, presents, and visions of the future through a series of experimental representational techniques and multimedia formats that begin to grasp the complexity of a non-Cartesian world.

One of Lokko’s curatorial projects, Guests from the Future, begins to do so by featuring underrepresented architects and artists, primarily from Africa, to present projects that delve into feminist, queer, and decolonial critiques of Western imperialism and its myopic gaze. For instance, Aziza Chaouni’s Modern West Africa: Recorded documents individuals’ relationships to architectural modernist sites that are unrecognized by UNESCO. Meanwhile, at the end of the Corderie, in the section titled Mnemonic, Chidirim Nwaubani and Ahmed Abokor present Looty, which mobilizes LiDAR technology to repatriate stolen art objects and intertwine them into digital financial structures. National pavilions similarly responded to gaps in Western epistemology, as seen in the Uruguayan pavilion’s En Ópera, which gives voice to a forest “deity” and its untranslatable indigenous knowledge through a computer-generated video opera.

In fact, the most prevalent media at the 18th Architectural Biennale is video. Large screen videos and black box theaters equally proliferate. Video, too, can be described as a virtual space, a type of heterotopic mirror capable of freezing, reversing, and prolonging time. Video makes tangible that which is otherwise unseen. Like a miraculous vision, it offers images from elsewhere that transport the viewer into another, parallel time and place. Whereas the churches once built to house relics sought to imitate the structures of Jerusalem, video, more directly, offers a mirror to another world, one that is equally real and unreal, here and there, then and now. Liam Young’s The Great Endeavor, for example, projects viewers into a near future by depicting a behemoth carbon-sequestration infrastructure. Presented in a black box, the curators ensure that there are no distractions and that, immersed in its audio-visuals, the viewer can almost taste and feel the ocean. Within the Corderie, video works are exhibited as though they are ethereal icons in the inner sanctums of temples. For example, MMA Design Studio’s Origins and Stephanie Hankey, Michael Uwemedimo, and Jordan Weber’s Synthetic Landscapes are projected on large screens in a nearly pitch-black room. Their light barely brings into relief the roof’s wooden truss structure, like that of a candlelit cathedral, while also pulling the visitor forward in space, inviting them to sit, linger, and be immersed in these images transported from colonial elsewheres.

Additionally, Lokko’s employment of the circular mirror room turns the visitor’s gaze inwards, prompting them to recognize their integral role within the exhibition and its processes of display, discovery, and discourse. It is a decolonial gesture. Rather than the colonized placed behind vitrines, the visitor is placed within the mirror to behold themselves. While literally a scene of self-reflection, it is more a moment of accountability: It is the moment of the pilgrim’s reckoning.

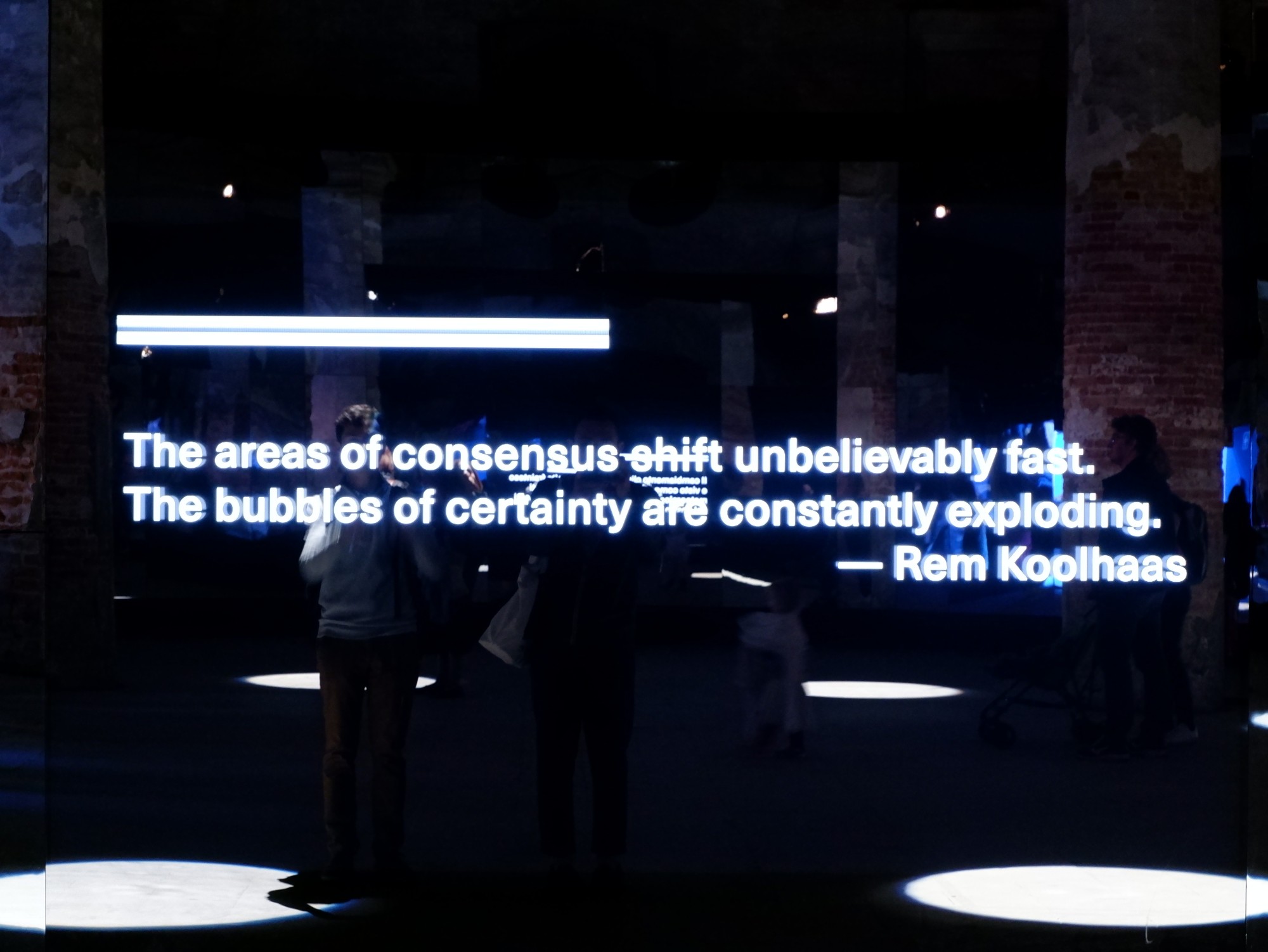

At the same time, Lokko reminds us that we are not alone. LED screens embedded in the mirrors display quotes from numerous architects, sociologists, scientists, and other cultural thinkers, ranging from Rem Koolhaus and Audre Lourde to James Baldwin and Paul Polman. The effect is that the quotes emerge from the virtual space of the mirror, from an ethereal other place, and then are displayed across the visitor’s reflection, imprinting upon them like a momentary tattoo. In both Christian and Buddhist traditions, tattoo ceremonies are often the culmination of pilgrimage, with the tattoo functioning as a prayer for divine protection. Francesco Lastrucci, “Inside the Thai Temple Where Tattoos Come to Life,” The New York Times, October 25, 2021; and Adelaide Mena, “Holy Tattoo: A 700-Year Old Christian Tradition Thrives in Jerusalem,” Catholic News Agency, July 9, 2017, https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/amp/news/36346/holy-tattoo-a-700-year-old-christian-tradition-thrives-in-jerusalem. Located at the beginning of the Corderie, these quotes placed upon reflections of bodies serve as a preparatory ceremony in which the voices of cultural “ancestors” come to guide the visitor. They will reappear again throughout the exhibition, both within the Corderie and the Giardini’s Central Pavilion where they are often located above doorways as reminders of the pilgrim’s journey.

II. Timing

While the hall of mirrors establishes a parallel heterotopic space, it also generates a heterochronous time. Foucault defines heterochronicity as “a sort of absolute break with… traditional time.” Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 26. He cites the cemetery, museum, and library as examples of heterochronous spaces, and we can include the exhibition space of the biennale in this category as it conflates various time scales while expanding others. For example, many of the installations, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa, BothAnd Group’s The Landscape Rehearsals, and Paulo Tavares’ An Architectural Botany, confront the archive’s authority, looking beyond its limited timeframes to uncover forgotten practices and marginalized voices.The ancestral voice, or the voice that speaks from beyond the archive, is a common theme throughout the Biennale. In unknown, unknown, Mabel O. Wilson, Meejin Yoon, Eric Höwler, Josh Begley, and Gene Han ritualize a reading of the names of enslaved people, mostly unknown to create a “cloud of sound.” At the Great British pavilion, the installation Dancing before the Moon “reflect[s] the ancestral practices and homelands of the artists and contemplate their legacies in Africa, Caribbean, and South Asian diasporas in Britain.” Curators Jayden Ali, Joseph Henry, Meneesha Kellay and Sumitra Upham sought to create “spatial portals” to diasporic communities, tying viewers and viewed together in a social “rather than economic” gesture. Similarly, in the Brazilian Pavilion, the symbol of the mythical Sankofa bird is evoked to bring the past into the present to build the future: “What unites these ‘Places of Origin’ is the way in which they carry the memorial dimensions of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian people, pointing to a process of retaking and repairing the representation of heritage;” Gabriela de Matos and Paolo Tavares, Terra. Often, this entails stretching the archive into the present to record surviving memories or—as seen with BothAnd Group—in generating new “memories” through reflective and iterative drawing practices.

In the hall of mirrors, Lokko generates heterochronicity by placing the reflected bodies in dialogue with micro- and telescopic scales. Hanging from the ceiling are images of what appear, at first, to be constellations. Projected on round screens and rendered in the same backlight as the wall quotes, they read as telescopic lenses. Yet, upon closer observation, the images could just as well be microscopic, depicting bacteria, viruses, or microfauna. While The Blue Hour freezes time, the micro-/telescopic lenses place the visitor in epochal time, framing the human journey within cosmic and tellurian epochs. The images’ ambiguity—whether constellation or microbe—disrupts conventional expectations and prepares the visitor for a journey that reveals time spans longer and more ambiguous than those defined by the West.

At eye level, the hall of mirrors places the visitor in human dialogue with themselves, with the reflections of other visitors, and with ancestral voices. At the intellectual or divine level of the ceiling, it places the visitor in dialogue with the cosmos, but in a way that reminds them that the earth, too, even its smallest inhabitants, is part of the universe and that humans are but one point on its vast scale of life.Many of the national pavilions, such as Belgium and Spain, also play with microscopic timeframes. In Belgium, mycelium is considered as a building material. In the Spanish Pavilion, videos by Marina Otero Verzier consider particles of the earth and their relationship to food infrastructure. In “Episode 5: Soil is Our Alien World,” microbes and parasites are elevated to the level of the divine when the narrator proclaims: “Unbury. Bury. Amen.” Later, the narrator asks, “Who owns the earth.” The answer, “witches and heretics,” re-sanctifies the earth by returning it to stewards who historically worshiped it. Ancestral voices, constellations, and microbes are all our guides: A scientific mode of reading the world is joined to a spiritual attitude. Cleansed of expectation, blessed by the ancestors, and reminded of our position in the cosmos, we can now pass into the exhibition space and make the journey toward enlightenment.

III. Returning

Pilgrimages are more than solitary voyages. As author S.D. Sykes states, “there was also a social element to this holy journey.” Sykes, “Did the Venetians Invent the Package Holiday?” Likewise, events, such as the Venice Architecture Biennale, are more than exhibitions; they function as social condensers that gather communities of architects, artists, curators, and other cultural thinkers into “a temporary moral community.” Barbara Kowalzig, “Festivals, Fairs and Foreigners: Towards an Economics of Religion in the Mediterranean Longue Durée,” 305. They steer disciplinary discourse. Adjacent and collateral events are equally important for bringing this community together to discuss the exhibition and orient conversation in other directions. The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, however, goes further by incorporating the voices of ancestors, the historically marginalized, the unknowable, and the non-human to participate in that community. In fact, these voices disrupt mainstream architectural discourse, and many of the collateral events gave prominence to such voices. For example, the Center for Art, Research, and Alliances (CARA) held a book launch just outside the Giardini for Emanuel Admassu and Anita N. Bateman’s Where Is Africa?, which challenges the geographic limits of “Africa” and proposes alternative methods for reading the diaspora through interviews and multimedia exchanges. Likewise, the Prada Foundation’s Everybody Talks about the Weather, continued the biennale’s discussion of climate change through an artistic lens.

The ambition of exhibitions like this biennale is not that conversations linger in the Giardini or alleys of the Arsenale. Like medieval pilgrimages, the goal is not the destination itself but the fruits of spiritual labor the pilgrim brings back to their community. As Howard explains, “The image of the Holy Land in Venice’s ‘imaginative geography’ was not only derived from the scriptures; it was also continually brought into focus by the oral and written narratives of returning merchants and pilgrims.” Howard, “Venice as Gateway to the Holy Land,” 89. Returning from a pilgrimage is just as, if not more, important than the embarkation. Whereas medieval pilgrims purchased relics as spiritual didactics, visitors to the biennale will return home with lessons of decolonization and decarbonization, permitting them—as the wall text for Lokko’s theme Dangerous Liaisons proposes—to “chart[…] new territories of professional and conceptual relevance and urgency.” Lesley Lokko, Dangerous Liaisons, in the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, Laboratory of the Future, 20 May - 26 November 2023.

St. Mark’s body was translated to Venice to sanctify the city and provide it spiritual power. It was a retrieval of the past and its myths. Lokko’s curation of the biennale is also a retrieval of another, forgotten, and ignored past and of its myths. This biennale arms the “moral community” of visitors with rediscovered and reimagined methodologies and epistemologies in the struggle against carbon imperialism. Simultaneously, it plays with different scales of time, stretching longer pasts into nearer futures, reflecting them into as many virtual possibilities as there are participating exhibitors. Lokko’s curation of the Corderie’s entry sequence strips the visitor of their expectations and prepares them to engage with this past. It displaces them from time and place, allowing them to immerse themselves in the times and places of the indigenous, the unknown, and the non-human. Pilgrimages removed individuals from real time and space such that they could experience a reflected spiritual reality whose divine lessons could then be returned to the community. Certainly, Christianity fabricated the image of a utopic Jerusalem, and the West a system of exclusion that othered its colonial subjects, yet, in Venice, truths from beyond have always arrived to guide the pilgrim. This biennale, with its cornucopia of media, artistic practices, voices, and sacred motifs, follows that tradition. If Venice was once a stopping point on the way to Jerusalem that transformed itself into a vision of its destination, then this biennale, which imagines an egalitarian future, should also be considered as a glimpse of that future already made present through pilgrimage’s discursive practices of embarkation, instruction, and return.

What remains to be seen, though, is how architecture’s “moral community” will be expanded so that interlocutors from the Global South can pilgrimage to Venice to participate on an equal footing with European and American colleagues, and not remain as others whose knowledge is placed behind glass vitrines. Indeed, this was a major controversy during the biennale’s opening week, as the Italian government refused to grant visas to a number of participants from Africa. Tom Seymour, “Venice Architecture Biennale Curator Criticises Italian Government for Denying Visas for Three Ghanaian Curators,” The Art Newspaper, May 19, 2023, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/19/venice-architecture-biennale-curator-criticises-italian-government-for-denying-visas-for-three-ghanian-staff. A larger reflection of the West’s exceptional isolationism, it calls to mind Igiaba Scego’s forthcoming book on Venice’s Black history. “In today’s public discourse,” Scego writes, “the continent is still seen as an isolated ‘garden,’ opposed to the ‘barbarism’ that surrounds it. An ‘us’ versus ‘them,’ a civilized being pitted against an uncivilized one. But who are ‘them?’” Igiaba Scego, “A Harlequin Europe: Unveiling Black Histories in Venice,” Koozarch, February 16, 2024, https://www.koozarch.com/essays/a-harlequin-europe-unveiling-black-histories-in-venice.

Indeed, who are they? As Scego reminds us, Venice has always been the site of “crossbreeding” cultures—one need only look to its Gothic-Byzantine-Islamic architecture to understand. Yet, walking through the Giardini and voyaging down the Arsenale, the number of non-white presenting bodies was sparse. If Lokko’s intention is to extend the invitation into architecture’s moral community to its actors in the Global South and its diasporas, then it only stands that these actors’s bodies, embedded with (and within) their own sacred knowledges, should be present to partake of that community’s privileges. It is not enough that their ideas be showcased in an international exhibition whose ocular methods are derived from colonial practices of encaging similar bodies in similar venues. Like how access to divine power was possible only by the literal presence of St. Mark’s body, the architectural practitioners of the Global South and its diasporas must be present in Venice, too. They must be visible, they must be attended to—otherwise, we risk colonial spectacle. Scego describes fifteenth century Venice as a “center of plurality” but also “a key for the future.” The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale frames itself in similar rhetoric, but in practice, does it maintain the singularity of hegemonic structures and their colonial gaze? Are the marginalized to remain abstracted “ancestral voices” meant to guide Western visitors rather than concrete interlocutors with whom we can converse, share new solutions, and pilgrimage together? If the future is to be plural, the present must be, too.