Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

‘Down to Earth, Cloud to Ground’: Towards a Poetic Infrastructure CriticismYidan Karel Li

‘Down to Earth, Cloud to Ground’: Towards a Poetic Infrastructure CriticismYidan Karel Li

Down to Earth, Cloud to Ground—The apparent synchronicity in the messaging of the Israeli and Luxembourger Pavilions may seem coincidental, but it reflects a shared contemporary examination of infrastructure and a similar research-based curatorial approach, shedding light on the evolution of architectural biennales. As the exhibition’s titles suggest, both national pavilions focus on large-scale infrastructure projects: Israel’s cloud computing data center and telephone exchange building that established its strategic position in the Middle East, and Luxembourg’s space mining program, a cornerstone of its ambition to be the pioneer in the exploration and utilization of space resources. Such massive infrastructure projects are often strategic investments for a nation, making it crucial to explore the motivations, stakeholders, environmental and resource impacts, and fundamental futuristic visions behind these endeavors. The in-depth analysis of futuristic infrastructure in the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale signifies the discipline’s evolution in the Anthropocene—a gathering of designers, artists, curators, and researchers from non-traditional architectural backgrounds delving into non-human constructions and territories beyond Earth and interrogating phenomena driven by national agendas and techno-economic transformations and their impact on familiar or alien territories, often with limited public awareness.

Infrastructure has always been a vital focus in environmental and architectural research. However, when used as a curatorial theme, it presents scaling challenges to curators. Whether as an academic showcase grounded in empirical and localized research or as an educational public event, curatorial endeavors that explore infrastructure require careful consideration of the complexity of infrastructure, spanning from the micro to macro scales and its position on the spectrum from academic to public. In this Biennale, the Israeli and Luxembourger national pavilions adopted different perspectives in their presentations.

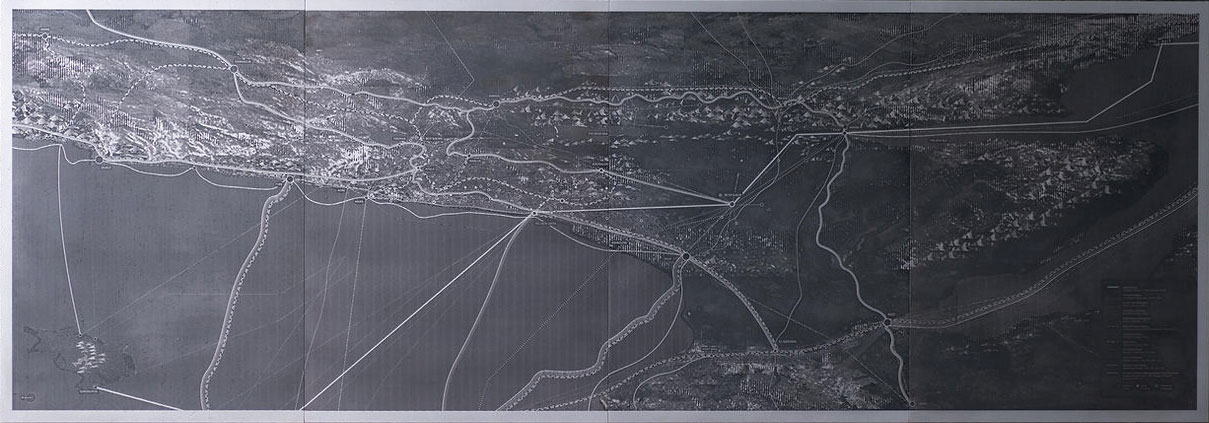

The Israeli curatorial team sealed its main pavilion—a 1952 glass-façade modern building by architect Ze’ev Rechter— to evoke the obscurity of machine-like and hyper-functional data centers and telephone exchange buildings. The curators brought visitors directly to the outdoor courtyard featuring five 1:50 scale concrete sculptures of the Telephone Exchange Buildings and a map called Passage Genealogy, critically examining the geopolitical reality of Israel’s fiber-optic cable construction projects.

In contrast, the Luxembourg Pavilion’s curators transformed the venue into a “Lunar Laboratory” and recreated the extraterrestrial environment, providing insights into the backstage of space mining operations. This is an interesting set of comparisons: one shrinks the “black boxes” that serve as research subjects,These black boxes are impenetrable structures that are connected by a vast network of cables, over land, underground, and underwater; Oren Eldar, Edith Kofsky, and Hadas Maor, Cloud-to-Ground (curatorial essay for the Israel Pavilion at 18th Venice Biennale). placing them in an open outdoor space, while the other condenses a whole industry operating in the vastness of space into a laboratory reconstituted within a dark indoor space. These curatorial strategies are rooted in research and exhibition mediation, directly influencing the presentation’s medium and means, as well as the audience’s perception.

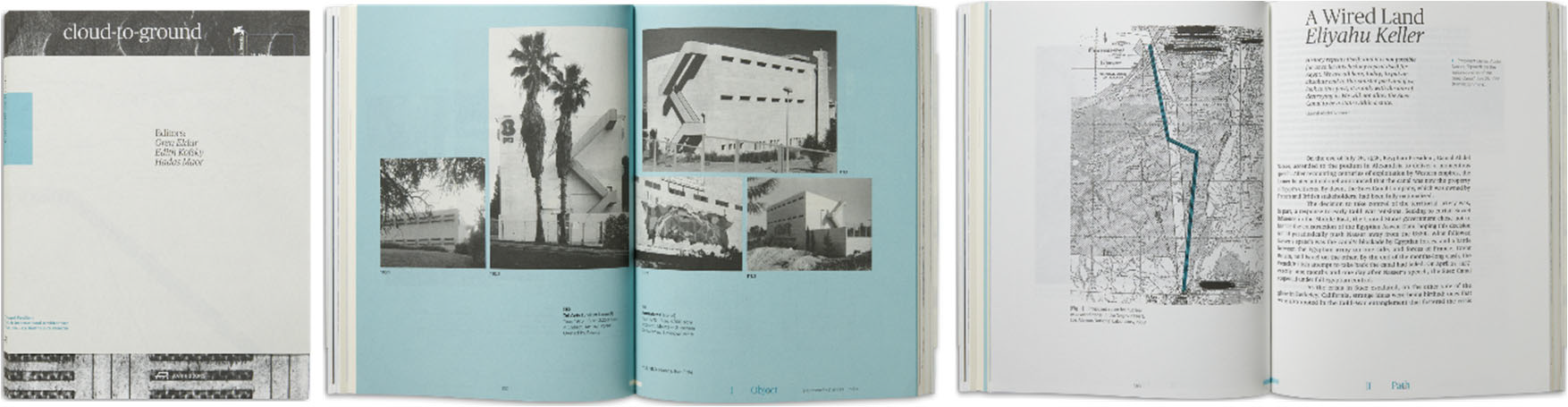

In on-site interviews, both curatorial teams emphasized the importance of translating recent academic research into the Biennale’s national pavilions. Oren Eldar, one of the Israeli curators, explained how the exhibition Cloud-to-Ground emerged in part due to Israel’s recently-announced national cloud initiative, the Nimbus Project. Edlar asked, “What is a national cloud?” Interview with Oren Eldar at 18th Venice Biennale, May 2023. Though a seemingly simple question, it is not a trivial matter. The Nimbus Project is a national large-scale initiative, jointly run by multiple governmental agencies that aims to provide comprehensive cloud services to the Government of Israel. As part of this vision, the government partnered with tech giant Google to establish a central infrastructure to provide cloud services for all government ministries.Israel National Digital Agency, “The Government of Israel Transitions to Cloud – the Nimbus Project,” press release, October 26th, 2022. https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/nimbus-landingzone. At this juncture, the curatorial team, consisting of architects and researchers, transformed research that had been ongoing since 2014 into a curatorial proposal with contemporary relevance. In their previous research, the team continuously studied various data centers and telephone exchange buildings within Israel. They compiled an index of these buildings, with a question in mind: How come these infrastructure buildings look so different when they are just infrastructure, storage for machines, and could have been duplicated?Interview with Eldar. It raised questions about the essence of non-human buildings.

The extensive research conducted by the Israeli team culminated in a publication bearing the exhibition’s name and featuring critical writings and interviews from various researchers. The book, divided into three parts—Object, Path, and Cloud—examines large-scale digital infrastructures as objects, the entanglements of infrastructure systems, and the metaphorical implications of cloud computing infrastructure. The essays offer insightful perspectives. For example, Eliyahu Keller compares Project Plowshare in the Negev Desert during the Cold War to Google’s Blue-Raman cable system, asserting, “Once again it is the Israeli desert that is marked not merely as a territory through which goods and information can be transferred, but rather as one whose transformation will remake geopolitical realities.”Eldar, Oren, Edith Kofsky, and Hadas Maor, Cloud-to-Ground (Zürich: Park Books, 2023). For more on Project Plowshare, see MacCabee, H.D. Publication, Use of Nuclear Explosives for Excavation of Sea Level Canal Across the Negev Desert.” https://www.osti.gov/opennet/servlets/purl/453701.pdf. Likeise, Lior Zalmanson explores the shift from human-generated data to machine-generated data and the implications for digital infrastructure, reminding us to remain vigilant about these imperceptible, underwater, underground, designed-to-be obscure structures and networks. These voices are particularly crucial today as the politics and complexity of architecture deepen with the proliferation of non-human buildings and digital infrastructure, making the Venice Biennale an essential platform for addressing these profound and urgent issues.

Similarly, the curation of the Luxembourg Pavilion is grounded in a relatively young national policy, one that provides a legal framework for commercial space mining companies to “develop the Luxembourg space ecosystem and create synergies with businesses and organizations outside the space sector, encourage the development of key skills and expertise, and develop Luxembourg and its space sector internationally.”Luxembourg Space Agency, “Space Policy and Strategy,” September 23, 2019. https://space-agency.public.lu/en/agency/mission-vision.html. The curators employed a highly interdisciplinary approach, conducting interviews with space agency personnel, private companies, artists, historians, and anthropologists, as well as on-site visits to space mining laboratories. They collaborated with five researchers to establish a space materials library and designed a related workshop to explore the political, economic, environmental, and racial histories of lunar materials. The term “unpack” was frequently used by curator Marija Maric. Indeed, the laboratory’s core function is to “unpack” the logistics, intricacies, and myths surrounding space mining, considering the moon not merely as a resourceful site but as a planetary common or through the lens of camaraderie.Interview with Marija Marić over Zoom, May 2023.

Managing extensive and multimedia materials while posing profound questions presents numerous challenges to curators and collaborators. Finding the appropriate interface and medium to showcase research findings, balancing accessibility, originality, and completeness when presenting research to the public, and navigating the delicate task of critically discussing national construction projects in a national pavilion’s context are all crucial considerations. Both the Israeli and Luxembourger Pavilions engaged in experimental approaches. The original plan for the Israeli Pavilion was to seal the building with LED screens and project an environment to make the pavilion seem to disappear, aligning with their goal of revealing the relationship between digital infrastructure and the surrounding environment. However, budget constraints led the curators to focus more on concrete sculptures and sound installations in the courtyard. Regarding the concrete sculpture, Eldar provided a poetic description: “For us, the keyword was always imprint. That for those buildings, the technology has a physical imprint on them. It’s not a subtle plan. They leave some traces, they are heavy…. We didn't want to create an architectural model because it is something else.” Interview with Eldar. The curatorial team sought to explore the weightiness of digital infrastructure in terms of materiality, which is why they did not use architectural terms but opted for a more monumental language. These hollow sculptures provided an excellent resonance for audio art, immersing the courtyard in a subtle rumbling sensation. The use of audio art itself was an experimental medium, inspired by the curators’ experiences with echoes in the buildings. The curatorial team captured such echoes and collaborated with a sound artist to create resonant audio inspired by sound artist Alvin Lucier's 1969 piece “I am sitting in a room.”Artist Alvin Lucier’s “I am sitting in a room,” is a time-audio piece, in which he recorded himself sitting in a room saying, “I’m sitting in a room recording myself” and kept re-recording the environment audio while playing the previous records. He repeated the process a couple of times and the sounds started to be abstracted, generating a very floating sonic effect. You can listen to it on YouTube. These audio elements, combined with the sculptures, created a subtle, immersive ambiance that overlays the presence of the buildings in Israel and the exhibited items in Italy.

Similarly, for the Luxembourg Pavilion, cinema was employed as a powerful medium, with a short film created by visual artist Armin Linke telling a story about resources, extraction, and territory—a domain in which the artist excels. This approach leaned more towards academia than public engagement, as initial visitors were often drawn to the compelling sense of space and might not spend extended periods watching the film.

This situation is not uncommon, and it doesn't necessarily frustrate curators, as this ambiguity is constructed, blending realistic space environments with fictional narratives. However, presenting research to the public remains a critical challenge for curators. As Marija mentioned, “We have to do something very consumable because audiences will just be there for two minutes. You need to make sure your message is so simple that it can be digested in under two minutes.” Interview with Marić. She touched upon the dilemma of researchers who are also curators, raising questions about when the role of a researcher ends, and the role of a curator begins—a systemic issue applicable to all research-based exhibitions in the Venice Biennale and beyond. Marija proposed her answer, highlighting that “the beautiful part is the exhibition becomes a space of not just consuming information but thinking together.” Interview with Marić. While this might not be a definitive answer, it offers a constructive perspective: When researching and thinking are perpetuated during the exhibition, and an exhibition becomes a platform for a large group of people exchanging information rather than a small group showcasing information, the distinction between roles becomes less critical.

However, it is undeniable that the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale serve as interfaces not only for information exchange but also for a natio’'s interaction with the world. In this regard, curators cannot ignore the sensitivity of their identities and positions, as they convey a national narrative. Curators need to find a buffer zone between raw research material and national narratives and mediate between stating facts and encouraging criticism. The authoritative nature of Israel’s Nimbus Project and Luxembourg’s National Space Mining Program, coupled with numerous stakeholders, amplifies the need for criticism but also complicates it. What we witness in these two national pavilions is a result of mediation—a form of poetic criticism. On a broader scale, this embodies the theme of this iteration of the Biennale. A Laboratory of the Future is a place where such experiments occur, where we explore not only the future of infrastructure and the built environment but also the future of research, communication interfaces, and critical methodologies. Just as Marija said, “It's important to remember that research is always very vulnerable and should stay vulnerable. We don't want to live in the moment of final big statements.” Interview with Marić. A Laboratory of the Future provides a nurturing environment, lens, and platform for these budding, radical, interdisciplinary, and vulnerable thoughts, from which constructive dialogues and patterns can emerge.