Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

Representing Coloniality/ Recording the Land: Interview with BothAnd Group

Representing Coloniality/ Recording the Land: Interview with BothAnd Group

Zachary Torres and Aaron Smolar met with the members of BothAnd Group to discuss their project The Landscape Rehearsals, which explores historic and contemporary relationships between the pastoral practices of Ireland and Nigeria. We chat about media representation, the difficulties of translation, and how some things just can't be captured in a drawing.

AC: Alice Clarke/ KR: Kate Rushe/ AOM: Andrew Ó Murchu/ JA: Jarek Adamczuk/ AS: Aaron Smolar/ ZT: Zachary Torres

Can talk to us a little bit about your practice, especially in the context of the exhibition?

I’ll just start with where we started from, as four architectural graduates from TU Dublin. When we graduated, we practiced in architecture offices, which were all building oriented. In 2015, all of the conversations around us changed to whether we should keep building or whether we should be rebuilding or reusing, or whether the landscape needs to be part of the conversation, and a more multidisciplinary approach emerged. By engaging in conversations with each other, we found that we all were moving towards an approach which was more interdisciplinary. And we saw landscape as a key part of the future for climate action and for how we wanted to practice. We started sharing readings and ideas and different kinds of references. And so we decided to put in a proposal for a small pavilion competition in Ireland, where we were questioning the purpose of competitions, which always seem to produce an object in the end. Instead of proposing an object, we looked towards practices like Lacaton and Vassal who approached the site, not just as something on which to build, but to actually consider what the site needs, and maybe it doesn’ t necessarily need something physical. In their project in Bordeaux, they proposed a maintenance plan. So we, too, proposed a maintenance plan for the community. Then, this project developed more into an interest towards the landscape in Ireland, which everyone perceives as this kind of green luscious place. But there's all these layers underneath it, which are the negative impacts of climate change. We started to question that, and we saw our roles as architects as key in the skills that we could bring to highlighting this and to kind of go towards a more active practice with more agency.

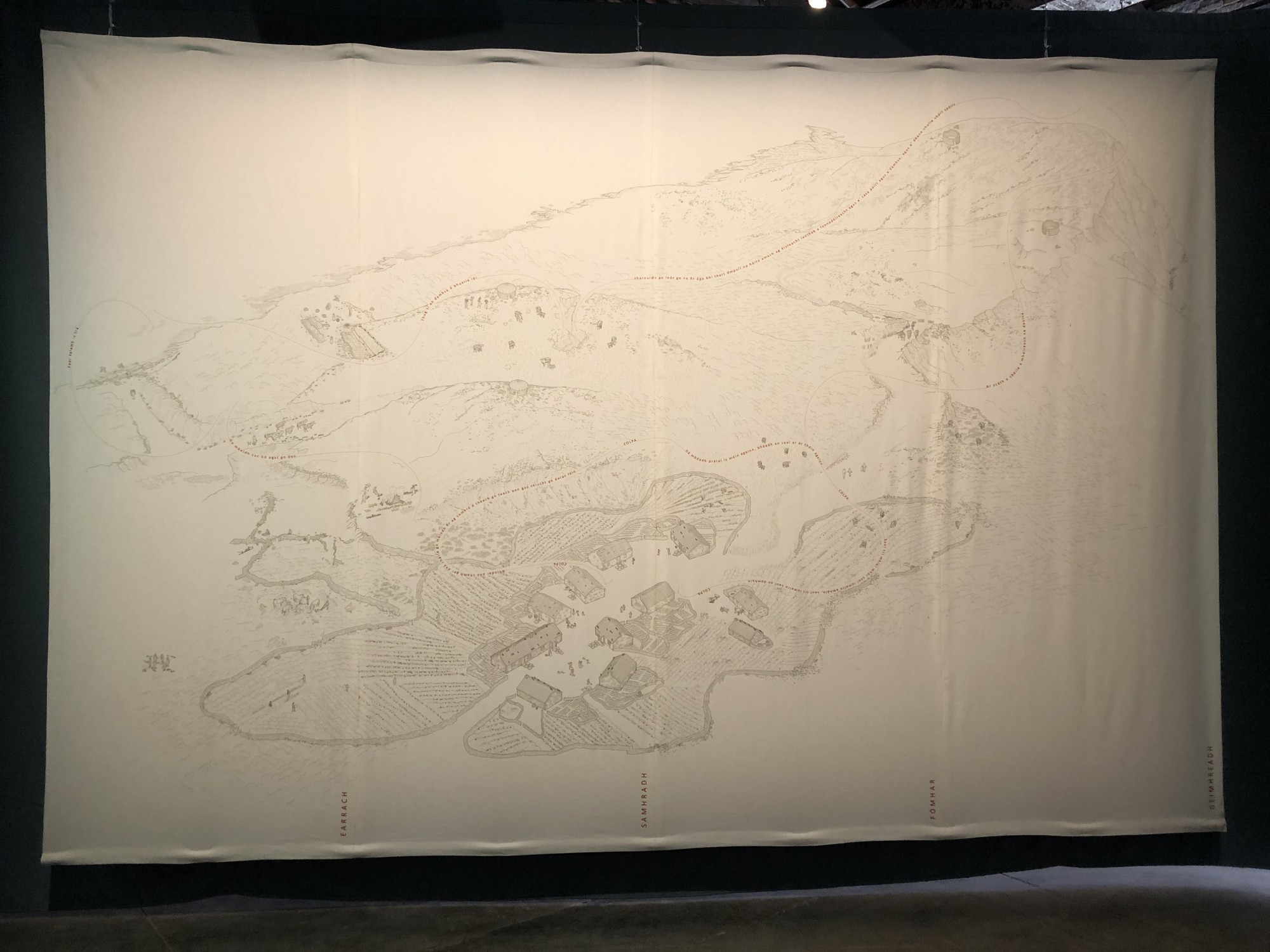

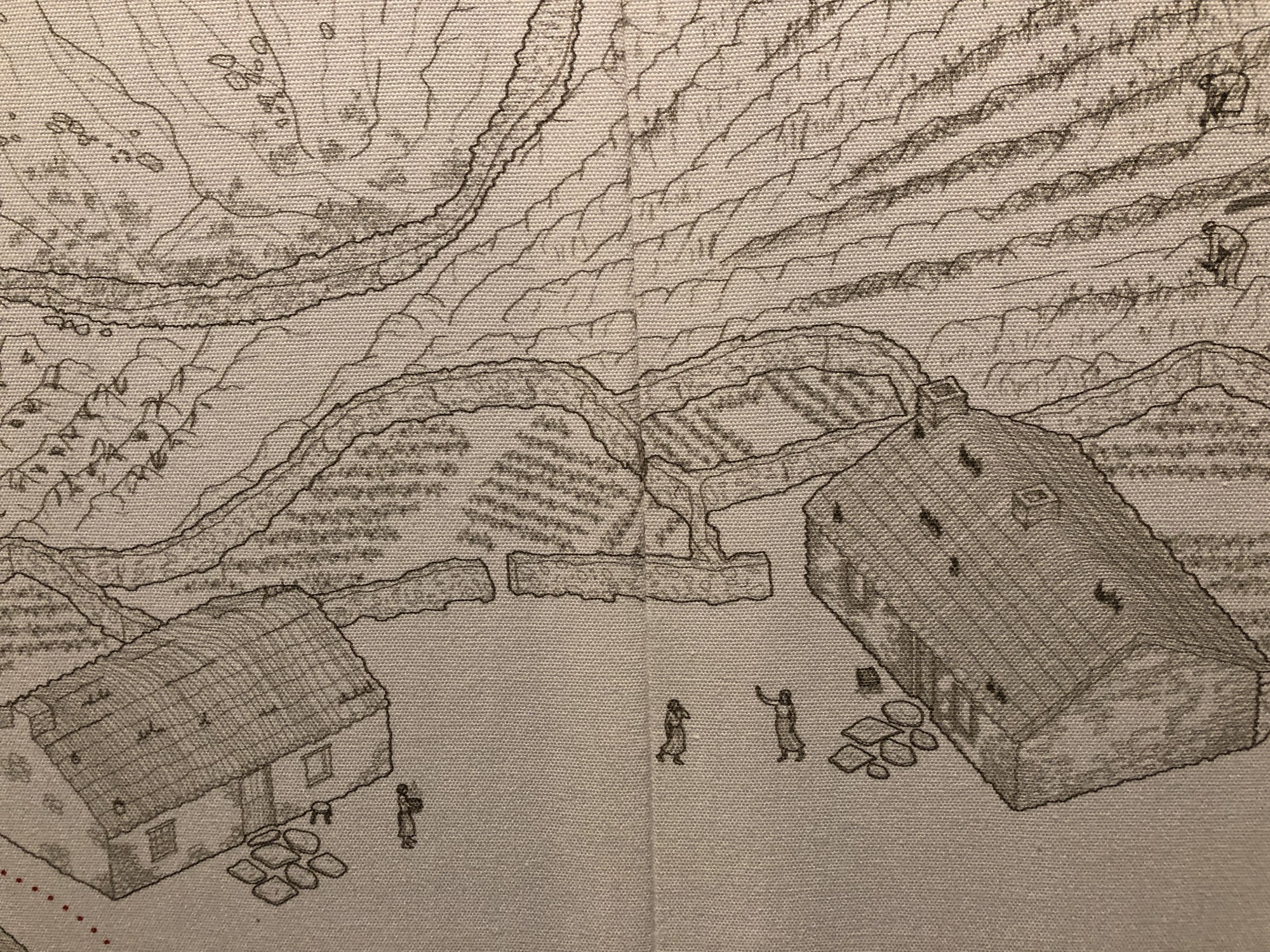

We officially formed in 2019. We did a few projects about food and agricultural monocultures. From there, we were invited to the Biennale,to be part of Food, Agriculture, and Climate Change. That aligned with what we were doing because we had just finished a project about a plate of food in Ireland. So we followed the interest of that project. We started this in about August 2022, and we collaborated a lot with the curator in special projects. We had about three meetings with Lesley Lokko and our co-exhibitors, Gloria Pavita and Magardia Waco, where we discussed what this exhibition could be. We all started with the same theme, but explored what we all thought that meant. Our project is titled The Landscape Rehearsals, and it’s an exploration of indigenous knowledge and practices. It's all about learning lessons for the future of agriculture in a warming climate. You can see behind us, this is a drawing of a indigenous practices in Ireland called colpa. What we found really interesting about this practice was that they managed resource allocation in fertile pastures of land in the west of Ireland. Simultaneously, we were looking at Africa, and in the exhibition you can see a film, which parallels indigenous practices in Nigeria. [The film and map face each other.] So we have a historic condition and we're also looking at contemporary indigenous practices in Nigeria. What’s really interesting are the shared, parallel practices. So in this film, you can see farmers and pastoralists where they practice transhumance, which is the seasonal practice of bringing cattle to higher pastures. Similar practices happened in the Irish context. So we wanted the platform to be an analogy to really explore this topic.

We started with the Irish practice, but they both were and are facing conflicts. For the Irish practice, it was eradicated by British colonization, which saw it as savage. Then in a modern sense, there's a parallel in Nigeria, where the practices are now being outcompeted by foreign investors, and Ireland is included in that. So in a modern sense, they're being colonized by globalization and by industrialized and corporate farming practices.

What’s interesting, too, in the documentary is you can see that there are two indigenous practices that are actually in conflict with one another. The pastoralists and the farmers don’t get on. We worked with an agronomist and landscape architect, Gbogboade Seun, who does advocacy work on the ground to try and build a relation between these two practices. It was great because we were able to collaborate with many different people for this project. So the project’s final layer is discourse. We interviewed specialists in economy, historians, and people working on land rights. When you stand beside the drawing, you feel that conversation, which describes the practices in the Irish landscape, but also the global understanding between the video and the drawing, Ireland and Nigeria.

What were some of the challenges you had in suturing these two practices?

It was actually quite natural at the beginning because we started out with this essay by Achille Mbembe describing Africa as the last frontier of capitalism. If you think of London as the center of the British Empire, then Ireland is actually the first frontier of capitalism, and the first kind of laboratory for the British to test colonial practices. We were looking for the kind of pastoralists in similar landscapes facing the same challenges that the Irish landscape had. More complexly, the Irish are now impacting Nigerian agriculture directly with their dairy imports.

I think the video is key in terms of Gbogboade’s work because he is quite active in terms of working with communities in Nigeria and making changes directly on the ground. Something that we wanted with this project was to engage directly with the community so that the conversation might develop. In Nigeria, it was important for us to work with somebody who was actively playing a role within the communities trying to resolve and highlight these indigenous practices.

The other challenge is that we had never produced a film. We were so comfortable with the drawing and the architecture part. The film, I think, was an amazing thing to have produced together, like even the translation and subtitles. We worked really hard with the video editor to get the narrative [right].

You mentioned that the Biennale s provocation helped to consolidate your practice in some sense. Could you talk more about where you see BothAnd Group going?

We’re constantly asking ourselves that, as well. At the moment, the drawing, the film, and working with people has confirmed that we really enjoyed this community engagement. We see that now as a key part of the process. Possibly that will inform how we’re practicing in the future. We’re still young as a practice, but, in terms of making changes, this is where we see our role as communicators within communities. Also one of our group is returning to landscape architecture school, so we’re interested in where his work will lead us.

(At this point, Jarek Adamczuk and Andrew Ó Murchú enter.)

Jarek and Andrew, Zachary and Aaron asked the question, how do we see our work evolving in the future? I was just saying that Gbogboade’s work with the film has really confirmed our process for community engagement.

Destination versus journey. We’ve done work in the past where we’ve been too focused on the final version, which some will say is utopic. Often in certain schools of architecture, research might be focused towards creating some kind of idea of the future.

You come to an end too quickly.

It’s all about the journey to get there. Currently, we’re thinking about food systems, food production, and sustainability more generally. And we’ve realized that by working with landscape architects on the ground in Nigeria, that actually, that stuff is quite grubby. It’s the hardest thing to do. And if we actually really care about all the things we’re talking about, that journey becomes about collaborating with the people.

We’re open to how our skill sets can be used in terms of working with those communities. For example, it might be drawings or mapping that’s part of this process.

For Gbogboade, he has a network of people, but there’s an issue with communication. We can help with the communication.

It’s kind of like being a co-initiator. We’re not saying, “Oh we can take over this project.” It’s more, “What skills can we actually add that are of value?” Even this film, I suppose for Gbogboade, is actually very useful to push his work further.

In this exhibition, the video is quite different. Biennales are often accumulations of lots of stuff, which last just for that moment. But we are saying, “How can we do things like this video that can actually be used for advocacy work?” For example, you can take this video to seek funding?

Also, he will be bringing the video back to the communities to start a conversation. The video involved these focus groups that he did, with the farmers and the pastoralists. He can go back with the video to show that this kind of communication between the two is possible and there is room for solidarity.

Since there is this participatory imperative, did this inform the choice to use video at all? Did the fact that the video would be coming back to these communities inform representation?

We saw the drawing as something new. There’s no drawing of this Irish practice because it dates to before the 19th century. There’s no way to visualize it. We thought that a drawing was the best way to rebuild it, to visualize something you can’ see in photographs or videos. It represents this hidden knowledge that we’re exposing. Then the video was important because at the moment, these practices are happening, so we employed a modern medium. You can go to Nigeria and see the practice happening, but also you see the people of the community talk directly to them. The people on the ground are the core of the project.

In the video, you can see that it does expose this conflict that exists between two communities, but we were very careful about how that was communicated. We didn’t want it to be overly negative, so there is some type of resolution at the end. We hope it’s a balanced presentation of those two communities.

From a curatorial point of view, we describe the drawing as being like the past and the video as the present.

The drawing, too, is a kind of an imagined ideal of all the [indigenous] practices that happened within this world.

I’m interested in how you describe the drawing as this kind of archival infill while also referencing Mbembe’s work.

Yeah, I think it was important for us that we didn’t just do a drawing for drawing’s sake, but that it has value in terms of going forward. So we’re hoping to bring it back to Ireland and have this serve as a model.

For academics, too, no one has ever communicated this information visually. We hope to connect to academic work that is not always tangible to the broader community.

We want to broaden the discussion to other fields.

So in a sense, you’re returning this knowledge to the public.

Yes, in a way. The drawing has many layers, too. You can see, for example, that the way we stitched it, that it represents the whole year, with the one on the far left being spring.

And is the dotted line representative of the transhumance?

The dotted line is actually this layer of practice called colpa, which you can’t represent in a drawing because it’s a balance between humans, animals, and the landscape. It’s this kind of carrying capacity of the landscape, in relation to the soil. The way that we represented it was true to the language. So these terms [written along the dotted line] are actually sayings that have been born out of this practice in the Irish language. What we understand is that the language actually represents a lot more in its original form. So colpa has so much more meaning in Irish than when you translate it and it becomes a sentence. There’s knowledge that is lost when you translate. So we thought that the best way to describe this practice if it’s not able to be seen, is through language. We’re all interconnected through this balance between landscape and people.

How did language and untranslatability transfer into the video work in the Nigerian context?

Similarly, maybe? We couldn’t translate the whole piece here, but we tried to give a kind of general description. Anytime we were describing the practices that were happening, we used the original language to describe it. In Nigeria, they also have words for how they practice, and in that one word, there’s a lot of knowledge. So that’s actually why we wanted to keep the interviews with subtitles. We didn’t want to have an English voice over.