Field Notes from the Pluriversity: Reflections on the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale

Snippets and Fragments

Snippets and Fragments

“Thank you for coming. It must be a huge effort for you to come to Venice. I hope your accommodations are humane.” –Jacek Sosnowski, Polish Pavilion Curator

“And what are the challenges we faced? Firstly, the challenge of the rolling scroll. Well, it's an interesting idea. Yeah, it's crazy to have a scroll that's scrolling 24/7 all day. I mean, all the time.

To have a pen that will keep marking. A pen that will keep marking so it won't dry up. We experimented with different types of pens, different thickness. How fast it rolls determines how long the mark is. Because every time it marks, it's a two-second application. So you notice from this machine to that one, this is a shorter mark. That one is a slightly longer mark. We also intended to change the pen to different materials, so over the six months, you get different marks.”–Aurelia Chan, Singapore Pavilion Exhibitor

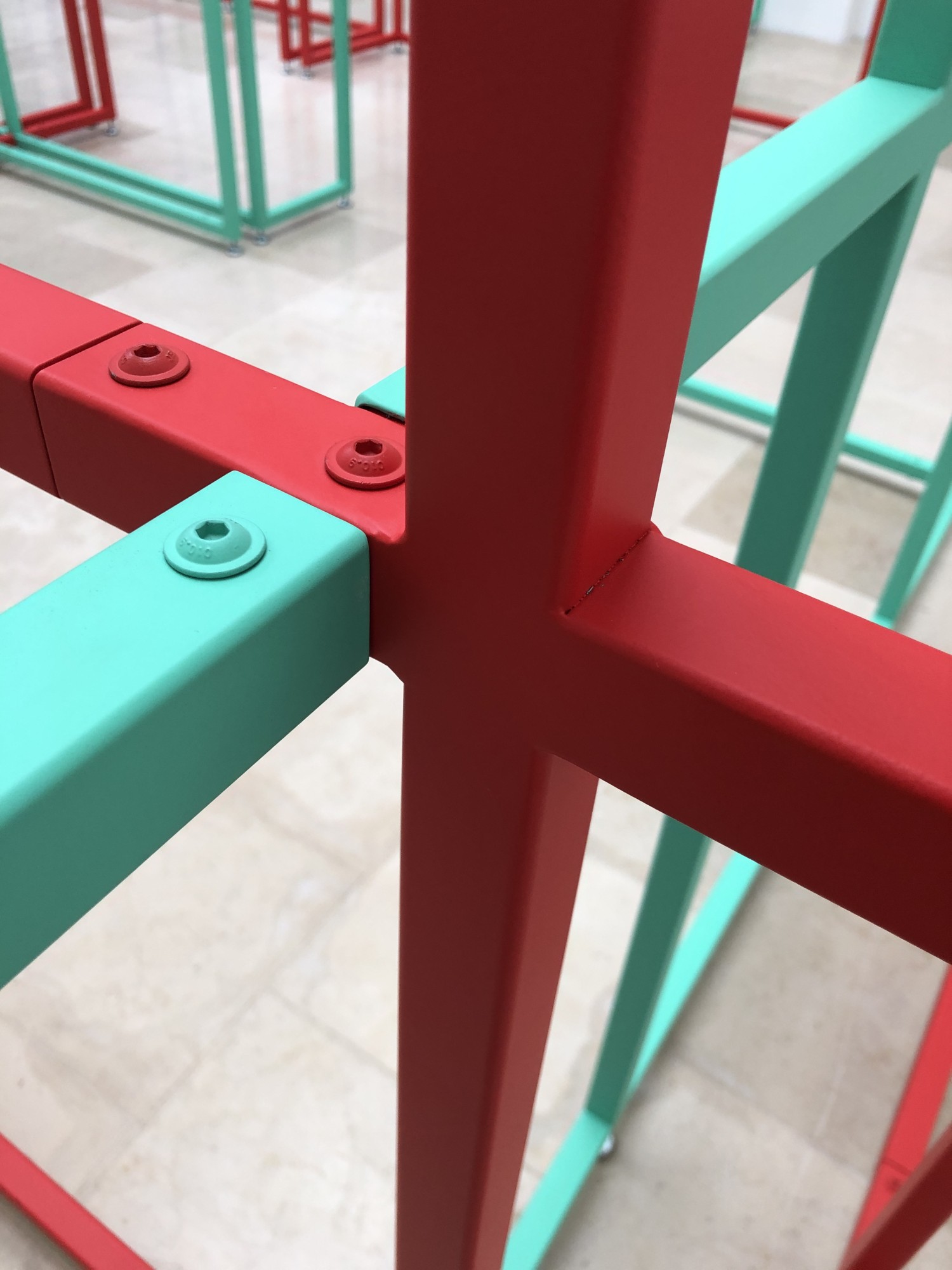

“With the three colors, we wanted to create the impression that you can decode structure. But the colors mean nothing. They don't convey any message besides the compositional and spatial, let's say the artistic. That's why it's a sculpture. We developed a special paint for the project that is 80% matte. The colors are bespoke, they are not off-the-shelf, so it doesn't look like a playground—I hope it doesn’t! But we also wanted it to appear to lose its thickness or shape in space. So, it’s almost as if you were in a vintage CAD program from the 90s. And so we wanted to create an experience, this machine for unknowing.” –Jacek Sosnowski, Polish Pavilion Curator

“We say: we don't know what the future is, we don't make any predictions. We are asking: what tools do we use in the laboratory, what kind of epistemology are we bringing into the laboratory? The sculpture is like a big question mark on the ontology of data. First and foremost, humans think in topologies, creating continuities, but machines work completely differently. Machines think in fragmentation, they create a bitmap that has a certain resolution to it, and it only mimics the effects of human activity. But there will be no creative machines, because humans are founded on a void—we are basically the only animal that knows all the time that it will die. Of course we can go to the Belgian Pavilion and ask whether the mycelium might be thinking of its own death because mycelium…well, that's freaky on many levels.” –Jacek Sosnowski, Polish Curator

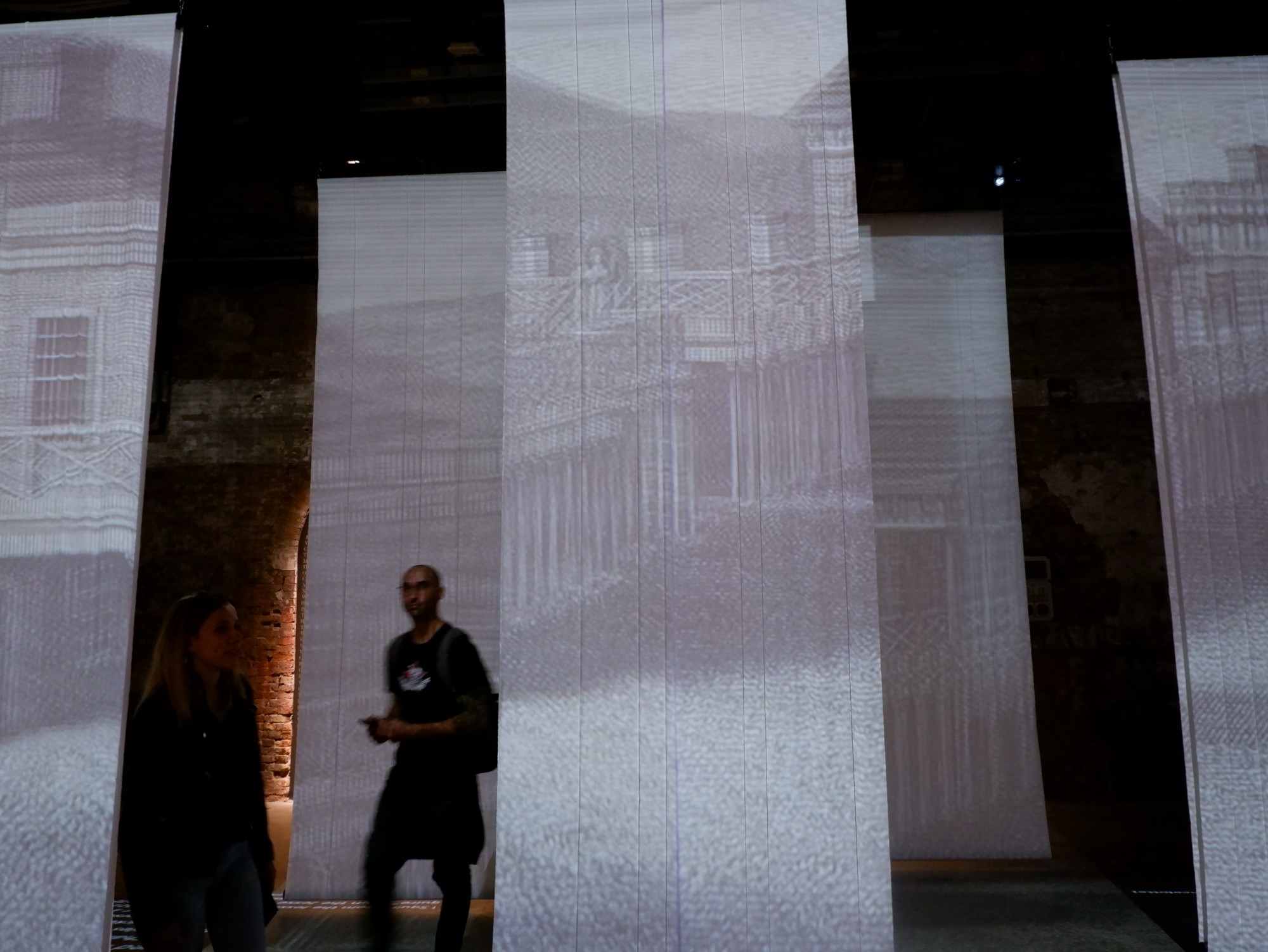

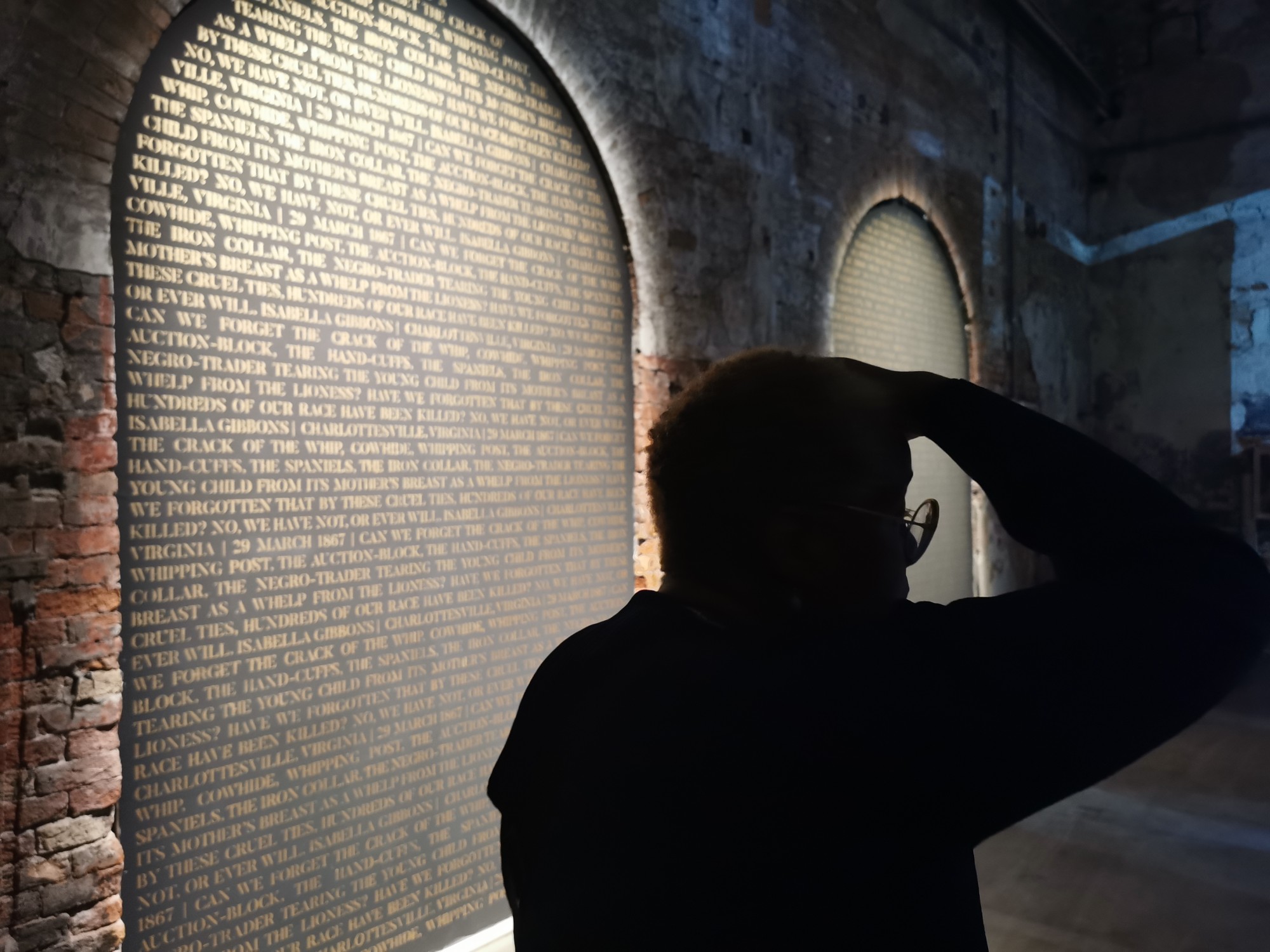

“They wanted us to address that aspect of captivity. But they also wanted to say, these were people. They lived, they had aspirations, they made community, they had families, they loved, they cried. So there's a duality, and as we began working on the project, we thought the archive has a duality, too. There's silencing and there's erasure, but maybe in that unknowability, there is refuge and liberation. So they don't have to be in history; they can be somewhere else. And that's how this question of unknowability and the fact we had a category on our spreadsheets called unknown, unknown, sort of linked up.”–Mabel O. Wilson, Mnemonics Exhibitor

“I think the greatest challenge of curating a pavilion is deciding what you really want to do. I think you need to have a very clear objective at the start. And then that will guide you through your process. As with architecture, as with anything. We wanted very much to respond to Leslie Lokko's theme and curatorial ideas. But we also felt that––I mean, after looking at the winning pavilions, we realized that maybe we were a bit too forward or too ahead of our time. We're still very Singaporean in the way we do things. So that's us. But we're very happy with the outcome. I mean, that's the best part.”–Aurelia Chan, Singapore Pavilion Exhibitor

“We will leave you with one final question: Should we build on our cultural heritage when we move to Mars? If you move to Mars, what will you take with you? Will you take any of your American culture with you? Or will you want to start afresh? Are there any other examples from your experience, from your studies, with which you could build a new world, a new dream, a collective?”–Lia Lapithi, Cypriot Pavilion Curator and Exhibitor

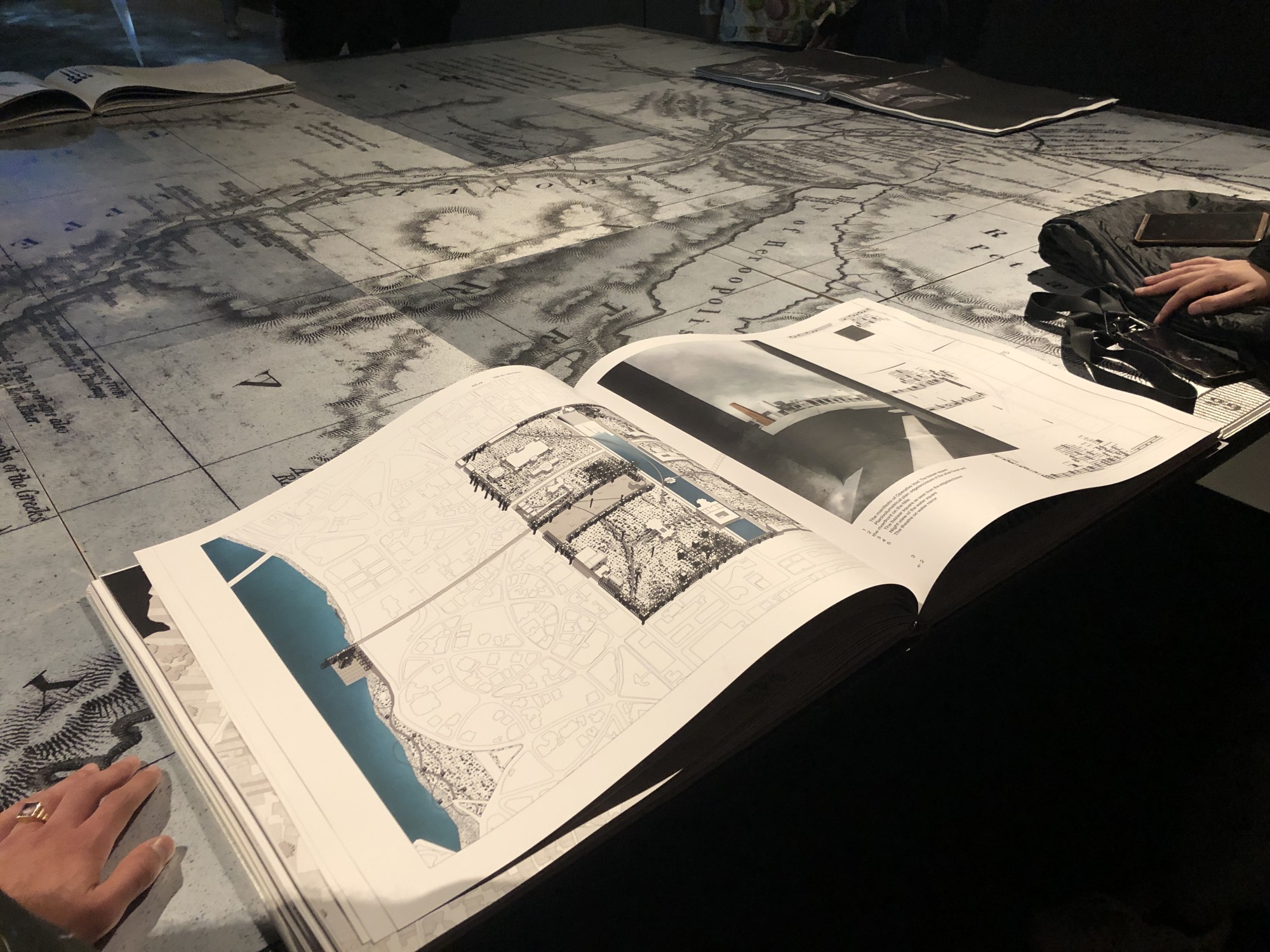

“In terms of the message, I think, you always need to think about who you are addressing. Who do you want to talk to? And there are several audiences that we would like to engage. Maybe the most obvious audience is the audience that, in a sense, paid for this, which is the Australian architectural community. In that sense, it's kind of a local thing. We address our own people. And what we want to say there is that we are engaging with these large political questions of power, space, representation, and meaning. We have these arenas of contestation and intellectual engagement that are entirely within the capacity of our profession to address or engage with. And we can do it intelligently. Indeed, we need to be doing this more. So it's really saying, ‘let's lift our game, guys, let's be more intellectually ambitious.’ As I said at the start, there's a kind of self image and also an outside image that architecture is a branch of the real estate industry, or construction industry, and it's not a vehicle for containing any kind of substantial ideas. There's strong ideas and clear intellects in the community, but it's just not broadly digested. It seems esoteric. So we want to bring this back to the architectural community of Australia. That's why an open archive is an invitation to everyone.” –Julian Whorral, Australian Pavilion Curator

“I think my work has conflicting aesthetic qualities, different conceptual, and experiential reactions. So being able to have repulsion, attraction, seduction, and disgust all tied up together—both in the forms and in the tactile, visceral, textural qualities. I think that communicates the complexity of plastics. For example, I made a crowd control barrier that's covered in children's toys, to see something where you have, on a kind of visceral level, an attraction to it because of your associations with this material that's been color-engineered to sell to children. So many people have come up to me, asking if the plastic flakes are some kind of candy. People from different countries have a different candy they associated it with. So it's like, ‘oh, these are like nerd ropes, these are sprinkles,’ or there's a British candy that someone mentioned that I've never heard of, and another German toffee material. But the idea that candies and plastics are being color coded to sell us a narrative, and then to make a very politically charged object out of that.”–Simon Anton, American Exhibitor

“So you find this kind of building [data centers] in many places. We chose one of them, in Be’er Sheva, which is in the desert, and it was just by the railway, so we recorded the railway noise. In an Arab town called Tira, we heard the muezzin and decided to sample it. So each sculpture has a different sample of resonance and a different sample of its setting. And then we played it with the exact resonance of the space—again and again. They became abstract but also started talking with each other. When you move around, they create a harmony, which is suitable because these buildings were not single objects, but mushrooms, above-ground manifestations of a vast network of cables, talking with each other already.”–Oren Eldar, Israeli Pavilion Co-Curator

“What is important is understanding that [decolonization and decarbonization] are connected. We have ideas of what they mean, but I think what is important, and what Lesley is also making visible, is that we need to go forward understanding that those can only be resolved or improved when they are both considered together. There is a big historical connection…finding some way that is better than now in this postcolonial situation where there is still so much injustice and inequity is also connected to a decarbonizing effort.”–Juergen Strohmeyer, Co-Creator of Plugin Busua

“I think that we are talking mainly about wood and timber construction, but the debate of ‘for and against’ wood is really popular now. We wanted to situate that discussion in our country because everything that you see in the video is currently happening. We must understand our reality and not talk about this debate as if we were from Europe or the United States. So we need to make our own version of this debate.”–Diego Morera, Research Director

“We understand the exhibition and the Biennale as not only the presentation of a project but as an opportunity to develop research and knowledge. There are several pavilion ‘types’ in this Biennale: there are pavilions in which architecture projects are the protagonist, and others in which there is no architecture. For us, this is a problem in the sense that we must dialogue with other disciplines and use this contamination, but the architecture must be the architecture, and this is the effort of our work, celebrating the projects.”–Marina Tornatora, Egypt Pavilion Co-Curator

“Peggy Deamer, a professor from the United States, described a dichotomy between architecture as one’s ‘calling’ and as ‘work.’ Deamer says that architects want to change the world while they are themselves working in precarious conditions—self-exploiting or allowing their bosses to exploit them. This question structured our team of young architects as they reflected on how they can change the world if they themselves cannot have a decent wage and work-life balance. Many of the people we surveyed wrote about these concerns, expressing that they tend to burn out because of conditions like financial instability. I do not know how it is for young practitioners working in the United States but in the Czech Republic, half of them work as freelancers [which makes their labor precarious].”–Helena Huber-Doudová, Czech Pavilion Curator